Trauma-Responsive Pedagogy: Building Resilience and Academic Tenacity in Students

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: Pedagogy

Discipline: Psychology, Theology

Many students face significant hardships, potentially leading to trauma. These challenges have the potential to derail them and keep them from fulfilling their dreams of completing a college education. While many challenges that students face are beyond our control, responding to them in a trauma-informed manner is not. Trauma-responsive pedagogy means that we adapt our teaching to support the well-being and success of students, showing empathy and understanding as they navigate the learning environment. Before the pandemic, economic upheaval, and social unrest of 2020 came to a head, Lubbock Christian University (LCU) began to prioritize the mental well-being of students by developing mindsets that lead to academic tenacity in an effort to bolster their resilience, their sense of belonging, and confidence in their own abilities to learn.

Academic tenacity refers to mindsets and metacognitive skills that allow students to look beyond short-term concerns to longer-term or higher-order goals and then withstand challenges and setbacks to persevere toward those goals. According to psychologist Carol Dweck and her colleagues, students who are academically tenacious feel apparent academic and social belonging, see school as relevant to their future, work hard with the ability to postpone immediate pleasures, abate intellectual or social difficulties, seek out challenges, and remain engaged over the long haul.1

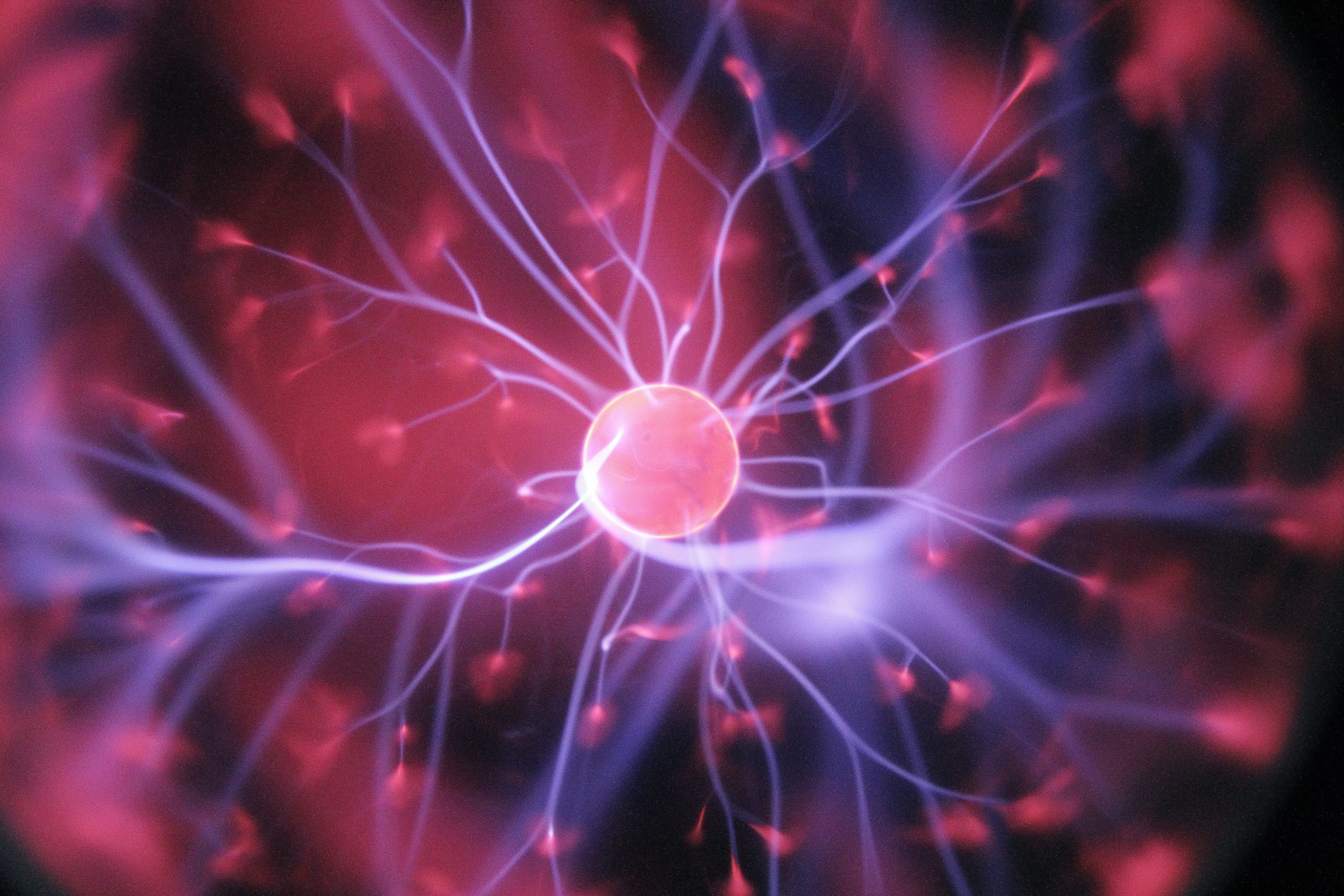

The mindset that students have about their own intelligence or other personal attributes affects their learning, their learning behaviors, and their tendency to persevere. According to Dweck in her book Mindset, a student develops their mindsets based on assumptions about the malleability of personal attributes, such as intelligence or morality.2 These assumptions are known as implicit theories of intelligence, and there are two: an entity theory and an incremental theory of intelligence. Some students embrace the entity theory of intelligence: the belief that these traits are fixed, unchangeable entities that we are born with. Others embrace the incremental theory of intelligence: the belief that attributes such as intelligence or morality are malleable. Findings in cognitive and neurosciences fully support the the incremental theory of intelligence.

Consideration of the affective results of trauma and stress in times of crisis is informed by the neurophysiology of learning and how stress affects it. When a brain is exposed to chronic stress or trauma, it changes both the chemistry and the structure of the brain. When a brain senses danger or insecurity, the autonomic nervous system kicks in and brain activity shifts from the prefrontal cortex to the hindbrain that detects threats and regulates survival responses. In the same way that the structure and function of the brain can change in response to stress throughout our lives, the brain can also change in response to learning experiences. The brain is adaptable, and intelligence is not fixed. Intelligence can be cultivated throughout one’s life, even into old age.

Most students demonstrate a fixed mindset about some traits and a growth mindset about others. Problems arise from a fixed mindset when it is linked to a student’s academic development and sense of belonging. Students with a fixed mindset are inclined to pursue performance goals rather than learning goals. They tend to worry about proving their intelligence and getting good grades, thereby preferring tasks that will verify how smart and capable they are. These students assume they were not gifted with specific intellectual capabilities and will often say things like “I’m just not a math person,” or “I can’t write; it’s not my thing.” When tasks become challenging or difficult, fixed mindset students often disengage or exhibit other avoidance behaviors, because they are ill-equipped to cope with failure. They get the sense that they are “not college material.”

In contrast, students with a growth mindset both see and believe the possibilities that are achievable through effort. They value hard work and tend to pursue learning goals. They focus on learning new concepts as well as improving their competence. When tasks become challenging, students with a growth mindset appear to experience less anxiety, put forth greater effort, and increase their engagement in the work at hand, accepting—and even enjoying—the challenge.

When practicing trauma-informed pedagogy, it is important to understand the development of tenacity requires more than possessing a growth mindset. Students must also be equipped with metacognitive skills in order to benefit from a growth mindset. Metacognition is knowledge about learning, as well as having control over one’s own learning. Students who exercise metacognition are able to assess and monitor their current level of understanding, predict their own performance on various tasks, and manage learning processes that lead to understanding. Students who hold a growth mindset tend to utilize more effective study practices and monitor their own learning.3 They are more likely to set learning goals and discover gaps in their understanding. They decide when and where to engage in learning tasks and demonstrate efficacy in both self-assessment and study habits. Growth mindset and metacognition are interdependent. Students need metacognitive skills to support a growth mindset and conversely need a growth mindset to fully employ their metacognitive skills. Accordingly, metacognition has been strongly linked with improved college GPAs, college readiness, and retention, making it all the more salient as we find ways to support students.4

Lubbock Christian University introduces metacognitive skills and a growth mindset for students and faculty. Incoming freshmen enroll in a one hour university seminar course within their major. All seminar instructors teach a four week unit on the brain and how it learns with an emphasis on developing a growth mindset. A learning academy for faculty helps them adapt their coursework and curricula based on what the cognitive sciences tell us about learning. Faculty study how people learn, including growth mindset and metacognition principles. Faculty then redesign courses accordingly. They incorporate practices that develop and support adaptive mindsets and introduce assessment measures that allow for a greater capacity of learning through practice. LCU is working diligently to create a campus culture that responds to student needs and strives to help students feel confident in their learning and a sense of belonging. This initiative transcends academia and has far-reaching implications in all aspects of students’ lives.

- C. Dweck, G. Walton, and G. Cohen, “Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills that Promote Long-Term Learning,” Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (2014): 4, https://ed.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/manual/dweck-walton-cohen-2014.pdf.

- C. S. Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (New York: Ballantine, 2006).

- D. T. Conley and E. M. French, “Student Ownership of Learning as a Key Component of College Readiness,” American Behavioral Scientist 58, no. 8 (2014): 1018–1034; François Cury, David Da Fonseca, Ista Zahn, and Andrew Elliot, “Implicit Theories and IQ Test Performance: A Sequential Mediational Analysis,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44, no. 3 (2008): 783–91; C. H. Jones, J. R. Slate, and P. C. Blake, “Relationship of Study skills, Conceptions of Intelligence, and Grade Level in Secondary School Students,” Study Habits Inventory and Thoughts about Achievement Questionnaire 79 (1995): 25–32.

- Conley and French, “Student Ownership of Learning”; S. Lamar and J. Lodge, “Making Sense of How I Learn: Metacognitive Capital and the First Year University Student,” International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education 5, no. 1 (2014): 93–105; P. Mytkowicz, D. Goss, and B. Steinberg, “Assessing Metacognition as a Learning Outcome in a Postsecondary Strategic Learning Course,” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 27, no. 1 (2014): 51–62.