The last year prompted faculty to recognize that, when thinking about trauma-informed care, we not only need to be aware of the trauma that students are experiencing; faculty are also experiencing trauma in ways that we need to address. It might not always be acute trauma, such as losing a loved one. Certainly, faculty are experiencing trauma in acute forms, but trauma is often experienced more subtly, like a low-grade fever that never goes away but nevertheless takes an inevitable toll on our bodies. Or, to use another example, our experience of the pandemic has been like sitting in an office or a classroom when a car alarm starts blaring outside in the parking lot. It immediately arrests your attention; then, you try to refocus on the task at hand, but the alarm just never stops. It is the never-ending annoyance that we can work through with effort, but the extra effort fatigues our bodies and taxes our nerves. And, since the threat of the pandemic never abates—since the car alarm in the parking lot never shuts off—we have no opportunity to rest and recuperate. This is how many faculty have experienced the pandemic. It has been a slow-building trauma that has accumulated over time just outside of our conscious awareness. We felt tired, but we couldn’t always articulate why. “Languishing” was a word some of us started to use to describe the experience,1 but we were not always aware how deeply it was affecting us vocationally, emotionally, and spiritually.

This experience led the Adams Center at ACU to be intentional about encouraging faculty self-care. It began with us asking questions about what makes for “good leisure.” We feel like we’re tired. We feel like we need rest. But what would good leisure actually look like? These questions resulted from a hunch that many of the ways I was trying to rest were not actually restful. So, we asked, what’s the difference between rest and escape? When I get home and want to “veg out” on the couch playing a game on my phone, is that rest or is that just escape? How do I feel after that activity? Am I refreshed, or am I still exhausted? Similarly, what’s the difference between peace and distraction? Or to put it another way, what’s the difference between Sabbath and sloth? These kinds of reflections helped us analyze our experience and think creatively about how to foster what we came to call “restorative recreation,” the kind of rest that would truly nourish faculty during this time.

In this process of reflection, I found Wendell Berry to be a helpful partner. Berry is an American poet, essayist, and novelist, and he explores Sabbath in all of these mediums. In his novels and short stories, one particular character, Burley Coulter, provides insights into Berry’s understanding of good leisure.2 Coulter is a bit of a rogue. He works, to be sure, but he’s also playful; he exemplifies the idea that, when things are rightly ordered, a flourishing life balances labor and recreation. I don’t expect that’s a revolutionary thought for most of us; we’ve heard about “work-life balance” before. But I think this is something especially important for faculty to remember because we can easily see our work as a calling and a vocation, something that God has drawn us into. That is a beautiful thing. I’m glad to have a job that feels meaningful and important and aligned with my spiritual gifts. But this rich meaningfulness can have a dark side. I can be tempted to pour my whole self into my work in an unhealthy way. My identity becomes too closely enmeshed with my work. Occasionally I need the reminder: it’s a job, and I need to balance my work in that job with other forms of recreation.

Along with reinforcing the need for balance, Burley Coulter also reveals another important truth about human flourishing: work involves play. He’s a playful worker. If one reads through Berry’s novels and stories, one repeatedly notices: Coulter is a playful farmer. That’s the kind of work he does, and that has been helpful for me to remember. When I’m feeling exhausted, going to class or working on a paper or meeting with students can start to feel like just the next thing I’ve got to do. Sometimes I need to remind myself: I get to do this. This is fun. I get to go and interact with students. I get to think about things that invigorate my mind, that are meaningful to me. Sometimes I need to pause and remind myself of that fact. Then I can see my time in class as a chance to play—not because it’s unserious but because it’s experimentation and exploration. The stakes are low; we can make mistakes and try again. And that’s a playful environment. That’s an enjoyable environment. If our work can be playful, it might change how we calculate the work-leisure balance.

We also learn from Burley Coulter that good leisure is not escape; it is not a distraction. Instead, it’s actually something that reinforces our place in the community. As a result, leisure is best when “local”; that is, when it connects us to the places and the people that are important to us. Similarly, good leisure is not escape because it is “productive.” Here, a little further explanation is needed. Often, we assume that productivity and leisure are mutually exclusive. We produce when we work; leisure, on the other hand, is rest from productivity. Certainly, we need to address our addiction to productivity in our culture. However, we should also recognize that often our hobbies are most nourishing when they involve making or creating something. Producing in this sense—being able to see and enjoy the fruit of our hands—builds us up. Good leisure, therefore, rather than distracting us from relationships or allowing us to escape the concrete places we inhabit, instead brings us closer to our community and anchors us to our place. Good leisure is communal, local, and productive.

With these things in mind, the Adams Center at ACU offered a series of sessions for faculty that we called “Be Kind to Yourself,” an intentional reference to the eponymous song by Andrew Peterson which became the theme song for the series. (If you haven’t heard the song, you should “be kind to yourself” and watch the music video in which Peterson performs the song with his son and daughter.3) We dedicated the first semester to exploring the questions about good leisure I mentioned above, and those sessions felt like most of the other sessions we offer. We would gather together to talk and think while eating lunch, though we would end each session with a specific challenge to practice “good leisure” in some way before our next meeting. At the next session we would gently hold each other accountable by asking about the challenge from the previous session. In the second semester, however, we decided to change our approach. We thought: rather than simply talking about it, let’s actually practice restorative recreation when we come together. So, we planned four different sessions that I’ll briefly outline below in case they are ideas that others can replicate on their own campuses. Also, they were fun and I’m excited to share them!

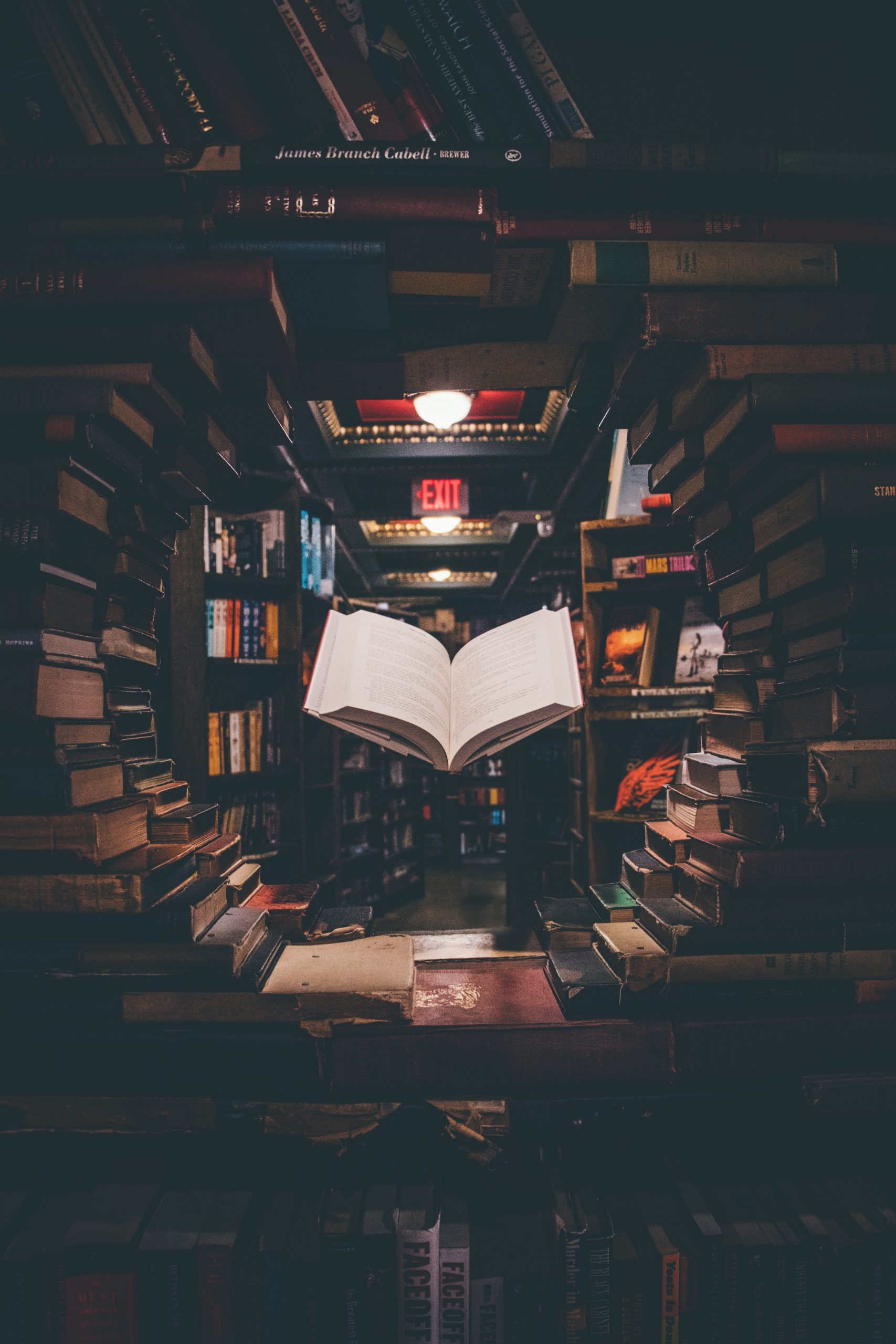

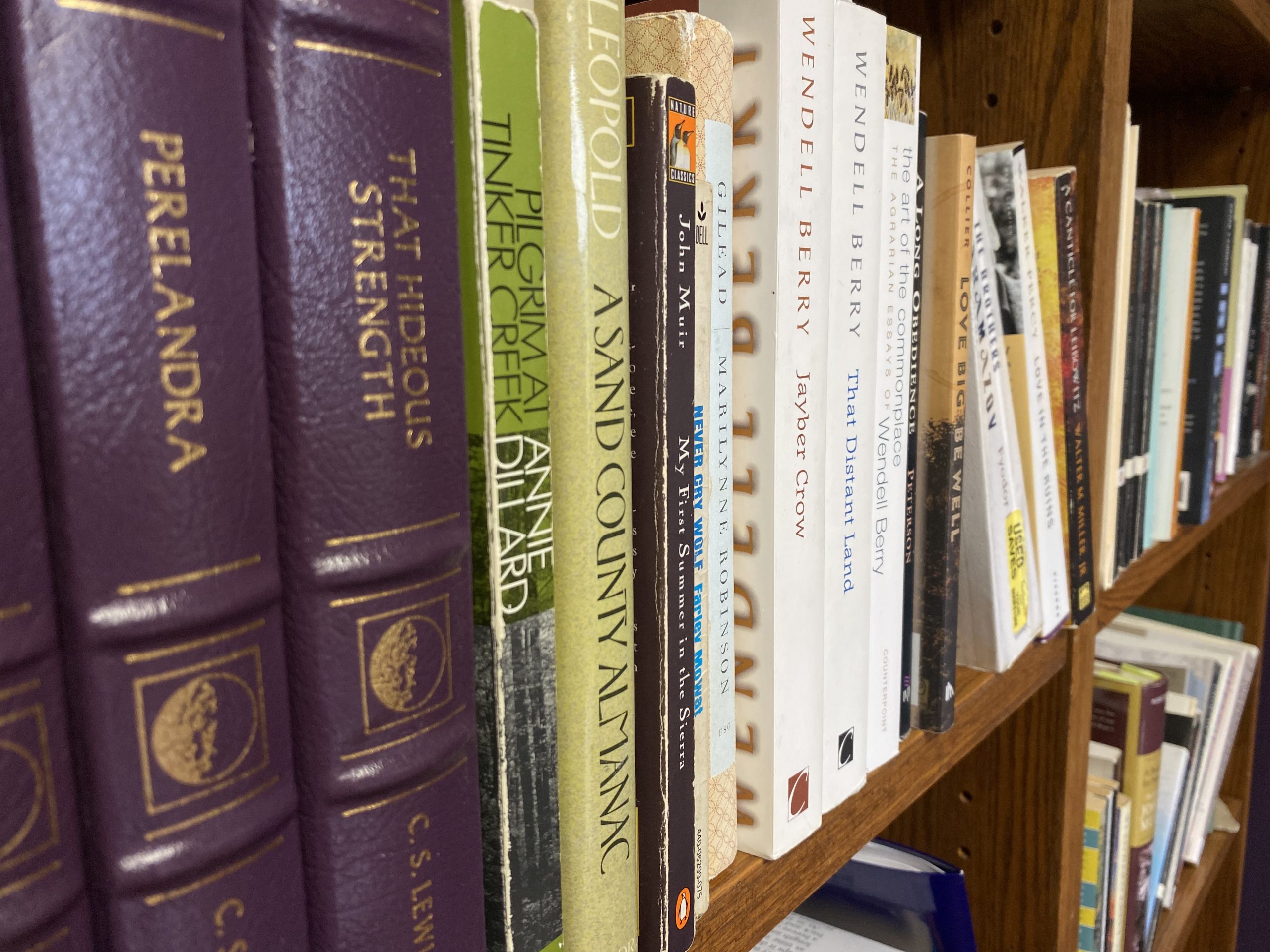

For the first session we invited faculty to bring excerpts from their “soul shelf.” The idea of a soul shelf comes from a book called The Flourishing Teacher by Christina Bieber Lake.4 In the book, Bieber Lake moves through the year month-by-month and addresses the needs faculty have at different points in the rhythm of an academic year. In the chapter for January, she encourages faculty to maintain a “soul shelf”; that is, a set of books, essays, poetry, movies, music, etc. that can feed the soul. The shelf might be metaphorical, but Bieber Lake encourages faculty to have a physical “soul shelf” where they can keep these important works because, she argues, faculty will need to access them during the doldrums they often experience in January and February. Because of their truth and beauty, the items on the soul shelf can nourish and invigorate us when we need it most. So, we invited faculty to consider: what’s on your soul shelf? Bring it to our first session of the semester and share it with other faculty. For the most part, people brought books, and we invited them to read an excerpt aloud to the group. Not only were we able to share something we loved with one another, but we were also able to hear about things that our friends and colleagues love. And faculty love books. So, in the end, we all left with a list of books to add to our wishlist.

For our second session, we offered an Ignatian meditation on the story of the Israelites receiving water from the rock while wandering in the wilderness. We first experienced this particular activity as part of the Advent Vespers series offered by Good Shepherd New York,5 and the meditation was so meaningful that we invited leaders from the church to offer the same experience for our faculty. Over Zoom, they guided our faculty through the story of the water flowing from the rock in the wilderness. They asked us to picture the story in our imaginations as we relaxed in silence with our eyes closed, prompting us to explore the story deeply by considering the things we would have seen, heard, or felt if we were there with the Israelites. By populating the story with these sensory experiences, the mediation heightened the emotional impact of the story and nourished us in a weary time of the semester.

In the final two sessions, we experimented with creative expression. First, Dan McGregor, a faculty member from the Department of Art and Design, led a group through a watercolor painting exercise. (We even bought a Bob Ross wig for him to wear during the session). We provided canvases, paints, and brushes for everyone, and Dan walked us through the whole process step-by-step. The end product was a beautiful mountain scene that we could hang on our office walls. For this experience of restorative recreation, not only did faculty stretch themselves by doing something creative; but, more importantly, we were able to do it together. The shared vulnerability this activity required deepened our relationships with one another.

In our final session, Shelly Sanders, a faculty member from the Department of Language and Literature, led a group through a walking and writing experience. For this exercise, Shelly would offer a prompt and send us on a short walk around campus. Then, we would come back and write. We repeated this process a couple of times as we slowly crafted our guided reflections into original poems. The session included faculty from a variety of departments across campus, and some had never written a poem before. But by the end, we had all written something and read it aloud to the group. The activity certainly pushed us out of our comfort zones, but it was nourishing to share the experience with colleagues. Once again, the shared vulnerability required by creative expression made for meaningful and restorative rest.

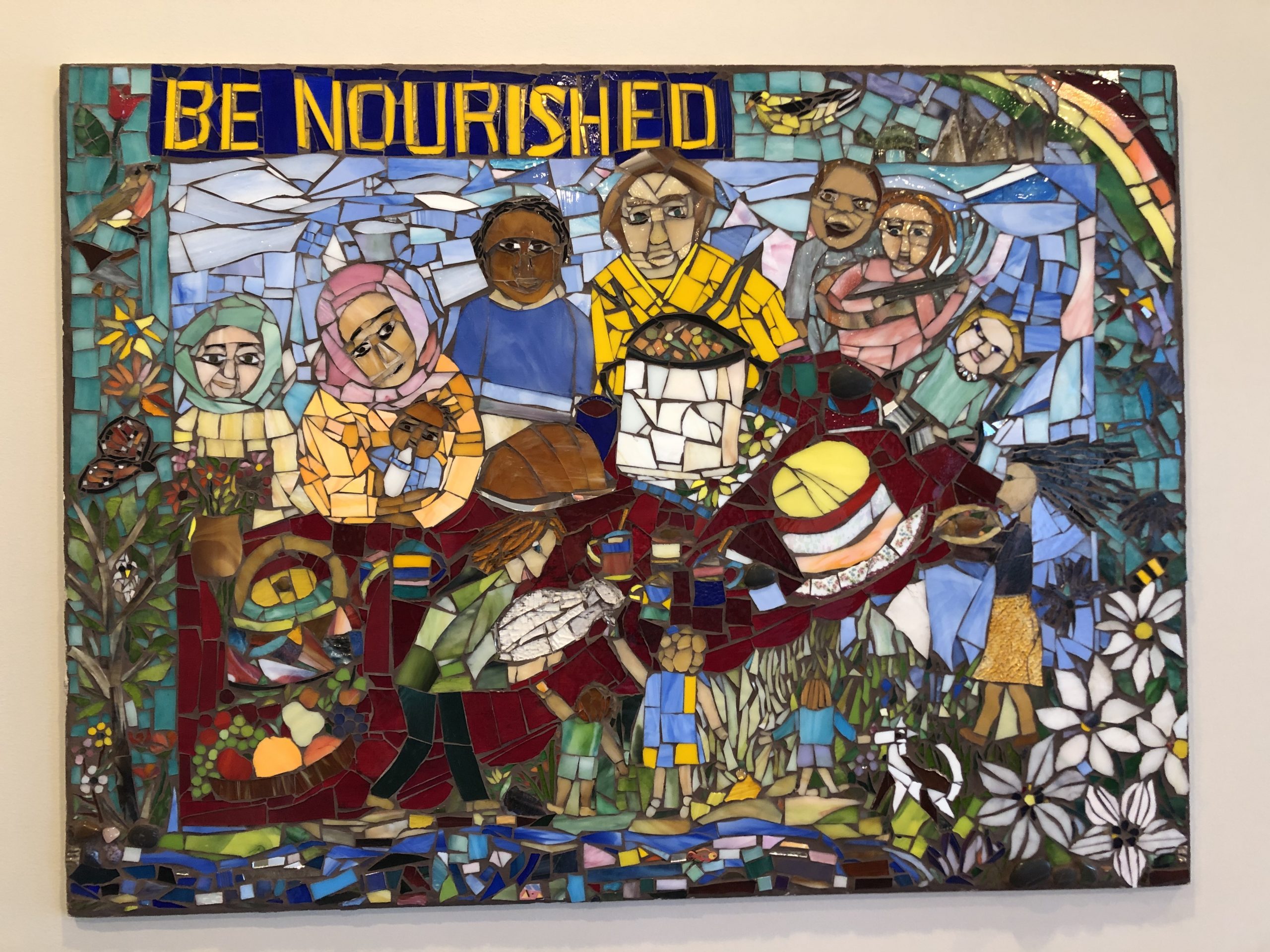

With the “Be Kind to Yourself” series, the Adams Center tried to provide experiences of “good leisure” for our faculty as a response to the widespread fatigue and burnout caused by the prolonged pandemic. To ensure that we offered opportunities for restorative recreation, we looked for experiences that would be communal, playful, and creatively productive. Feedback from faculty indicated that these sessions were rich and meaningful experiences. They were a way we could care for our faculty (and help faculty care for themselves) in the midst of trauma so that they might be nourished and strengthened to support their students through their own experiences of trauma.

Article Featured Image: Clifford Barbarick’s actual “soul shelf” in his office at Abilene Christian University. Image courtesy of Clifford Barbarick.

- Adam Grant, “There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing,” The New York Times, 19 April 2021.

- See Ethan Mannon, “Leisure and Technology in Port William: Wendell Berry’s Revelatory Fiction,” Mississippi Quarterly 67.2 (2014): 171–92.

- “Andrew Peterson—Be Kind to Yourself (Official Lyric Video),” YouTube, https://youtu.be/sYiM-sOC6nE.

- Christina Bieber Lake, The Flourishing Teacher: Vocational Renewal for a Sacred Profession (IVP Academic, 2020).

- You can learn more about Good Shepherd New York at the church’s website: https://goodshepherdnewyork.com.