Tom Olbricht as Historian

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: In Memoriam

Discipline: American Religious History

I am grateful and humbled to pay tribute to the significance of the life and work of Tom Olbricht for Churches of Christ, the Stone-Campbell Movement, and Christ’s universal Church, through his multifaceted scholarship and leadership.

In preparation, I read many of Tom’s articles and essays, surveyed his autobiographies, and listened to recordings in which he and others spoke of their scholarly life as members of this part of Christ’s church. I was especially struck by a section of his 1980 essay titled “Understanding the Church of the Second Century: American Research and Teaching 1890–1940,” published in a Festschrift for Stuart Dickson Currie. In it Tom reveals, I believe, his deepest convictions about why he engaged in the discipline of church history. Early in the article he quotes a statement by Phillip Schaff from his History of the Christian Church that reflected his own personal convictions:

A church history without the life of Christ glowing through its pages could give us at best only the picture of a temple stately and imposing from without, but vacant and dreary within, a mummy in praying posture perhaps and covered with trophies, but withered and unclean: such a history is not worth the trouble of writing or reading.1

In his hermeneutical autobiography Hearing God’s Voice, Tom remarked that though the major framework of God’s grace and love may sometimes get faint in the details of the biblical narrative, “one is compelled to backtrack and pick it up again.” The same might be said about Tom’s historical work. While Christ’s love and the human transformation into the image of Christ is sometimes obscured by the details, for Tom this was always the true reason for why one does church history.

In the 1980 article, following a similar line of thought to that later expressed in his autobiography, Tom characterized Schaff’s successor, Arthur C. McGiffert, as “perhaps more than anyone else, [the one who] paved the way for scholars to interpret church history in the manner they believed warranted by the evidence rather than according to confessional positions and doctrinal commitments.” He concluded the study with the judgment that church history was “Born to meet a particular need—the training of ministers—and maintained because it produced useful comment from the past upon the present.”2

Tom’s unflinching pursuit of truth, in Stone-Campbell Restoration movement history, theology, rhetoric and biblical studies, was not bound by a blind loyalty to party lines—on whatever side the lines might fall. Yet his love for his religious heritage was solid—he did what he did to strengthen the churches of that heritage, to bring to the forefront what he saw as the point of the Bible, the point of faith in Christ, of Christianity; a purpose he felt was often obscured by the way we understood scripture and a triumphalist view of our own history.

While that 1980 Festschrift contribution was focused on the study of the second century for the purpose of correcting and nurturing the contemporary church, I believe his statements were applicable to all of his work in church history (as well as his other scholarly work). Those commitments become clearest, perhaps, in his three autobiographies,3 as well as in his Old Testament and New Testament theologies, He Loves Forever and His Love Compels.4 In Hans Rollmann’s 2004 Restoration Quarterly article on Tom as a theologian, he draws from Hearing God’s Voice to demonstrate Tom’s belief that interpretive skills should be directed to uncover “the story line in Scripture” that “casts a long shadow over the individual facts.”5 Tom is clear in his conviction that the disclosure of God’s mighty acts for humanity and their abiding meaning was the point of scripture, and the point of the study of scripture was to discern that truth. Again, I believe that was also the point of church history for Tom and of his work in that field.

In his discernment of the “major framework” of Scripture—what he called in Hearing God’s Voice “a scheme of redemption” that embodied God’s love and grace6—Tom insisted that the Bible is the ground and theater of God’s loving action and self-disclosure in history. In Rollmann’s words, for Tom “The mighty loving acts of God and their interpretation was the true center of the biblical story. He moved beyond his Harvard teacher G. Ernest Wright in considering the authoritative interpretations of these acts provided in scripture of importance as well since they disclosed the meaning of God’s mighty acts.”7

Carl Holladay in his careful study of Tom’s work defers to “specialists in Restoration Movement history like Richard Hughes, Newell Williams, Jerry Rushford” and me as being in a better position to interpret the contours and main contributions of Tom’s scholarship to this field of study. However, I believe that Holladay is correct in his judgment that much of Tom’s work in Stone-Campbell movement history reflected detailed knowledge of specific individuals and episodes, or of how the concept of Restoration took shape in specific times and locations.8

Holladay’s assessment of Tom’s exegetical work was that his interests and writing tended to be quite broad, illustrated by such Restoration Quarterly articles as “The Bible as Revelation” and “Inspiration and Biblical Criticism,” not close exegetical studies characteristic of biblical commentaries.9 Taking Holladay’s evaluation of Tom’s historical work, it might be described as the opposite. That is, he delved deeply into specific characters, places and events but did not write in a broader way; that he was focused more on the local than the big ideas in the history of the movement. David Baird reflects that evaluation in his review of Tom’s 2019 book, co-written with Jim McMillan, on The History of the Restoration Movement in Illinois in the 19th Century. Baird calls it an encyclopedic study “that will please denominational scholars and readers as much as local and family historians,” concluding that its most notable strength is its detail.10

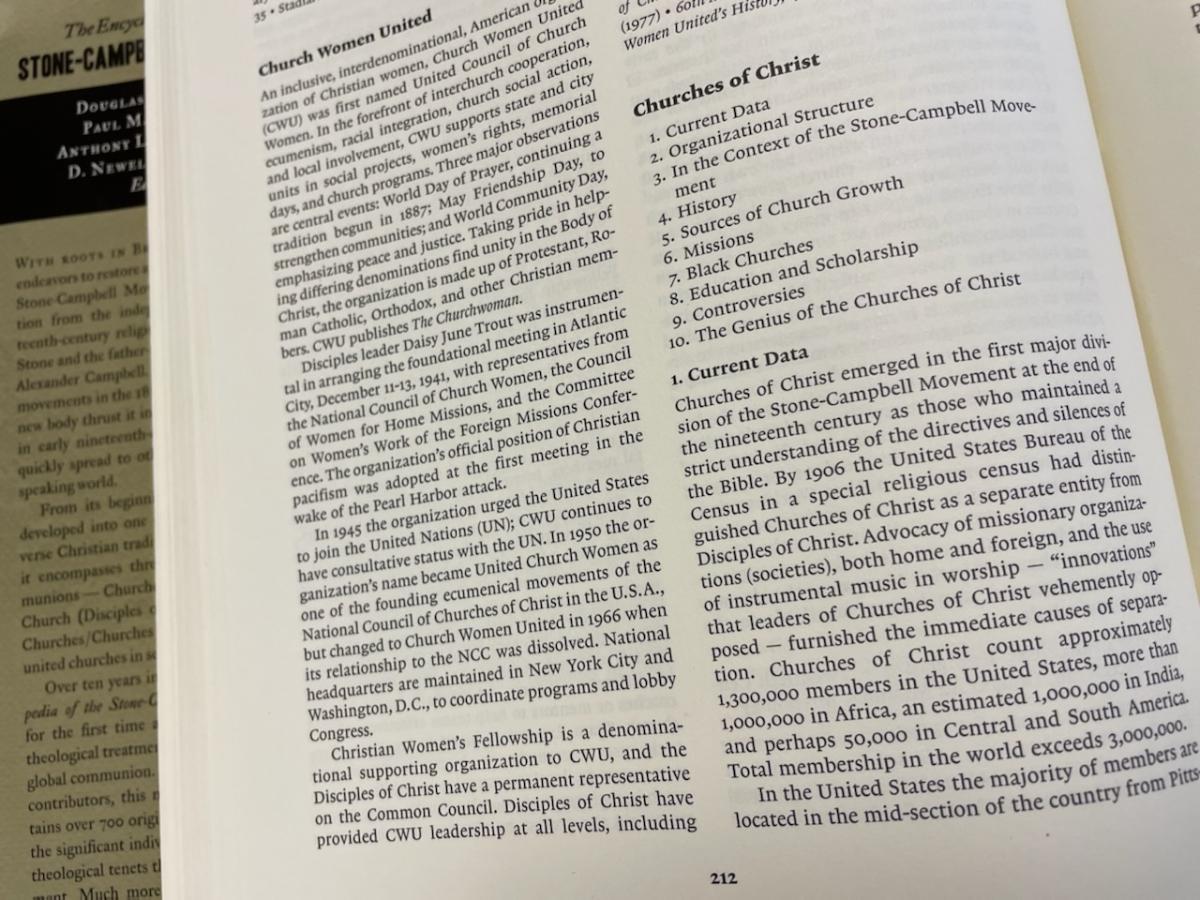

I think it is accurate to say this about Tom’s historical work generally. Another example might be found in the 27 articles Tom contributed to the Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement (a number probably exceeded only by some of the general editors). Tom wrote pieces focused on individuals like Abner Jones, Moses E. Lard, David Dungan, Samuel Rogers and G. C. Brewer, as well as institutions and publications like Ibaraki Christian College, the American Christian Bible Society, La Voz Eterna, and the Christian-Evangelist. Yet on the other hand, he also wrote the major sweeping articles on “Churches of Christ,” “Hermeneutics,” “Theology in Churches of Christ,” and “Worship in Churches of Christ”—all detailed, yet broad and contextualized.11

I also agree with Holladay that it might be tempting, since Tom’s interests were not confined to one specific discipline, to see him as a generalist who did not gain a mastery of any discipline. Holladay goes on to say, rightfully, that Tom was a generalist, but managed to achieve a remarkable mastery of the three fields he worked in because he saw how each related to and helped make sense of the others—in light of the underpinning of the story of God’s grace, love, and redemption.

In the 2003 Atlanta conference on Scholarship in Churches of Christ at the annual meetings of the AAR and SBL, Tom remarked that he had gone into the field of rhetoric and rhetorical criticism when he realized upon arriving at Harding that there were more engaging ways of preaching than what he had been used to. (He also made the claim that he had probably slept through more sermons than anyone else on that panel.)12

This is another reflection of the fact that in all of his scholarly work, Tom was looking to strengthen his church tradition—his people—in the faith, not in any kind of exclusivist way, but in order to help people inside the tradition to know and grapple with it as a part of their spiritual growth. He also sought to help those outside to understand us in Churches of Christ without dismissing us as merely a closed, exclusivist, fundamentalistic group, but one with a rich and diverse heritage connected intimately with the stories of scripture, American Christianity, and the spread of Christianity to become the global tradition it is today.

The historical/theological enterprise for Tom was never merely an academic pursuit. It was always done in the service of faith, in the service of the church. And it was done fearlessly and without holding back from pointing out where he believed people and events were working against the advancement of the understanding of God’s grace and love as the point of the Bible, and the point of his scholarship on the history of Churches of Christ. Tom did much historical and theological work in his autobiographies—they actually became significant conduits for his teaching. I must confess that sometimes I was a little uneasy about Tom’s frankness as he related his life’s experiences; but these accounts in my opinion did not come across as having malicious intent. He was simply telling what happened as he experienced it in light of his commitments.

In the 2003 Conference on Scholarship in Churches of Christ, Tom told the story of becoming friends with another faculty member when he was at Penn State who asked him what Churches of Christ believed. She told him that she had asked a neighbor who was a member of a Church of Christ the same question, and after thinking for a while the neighbor said, “we don’t believe in instrumental music.” The colleague told Tom, “I think you must believe something more than that.” And he proceeded to explain to her some key beliefs.13

Certainly, as much as anyone else, Tom thought seriously about who the Churches of Christ have been and who they now are. He was asked to write the major article on Churches of Christ for the Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement—and he did so, keeping in mind both that member who had no language to adequately express what her faith tradition believed and the colleague who was an “outsider” but who genuinely wanted to know something about the tradition’s theology and practices. I certainly knew of no one else whom I trusted more than Tom to write that crucial article, and he produced a significant piece that has helped thousands of insiders and outsiders know something about the Churches of Christ.

Twenty years ago Tom and I, along with Richard Hughes and Ed Harrell, co-taught a graduate course on Stone-Campbell history at ACU. His good-natured sparring with Ed Harrell in the class, in our meals together outside the classroom, and in the Conference on Scholarship in Churches of Christ was usually fun and stimulating, though at times it made me uncomfortable. Here again, in the classroom and in his interaction with his colleagues, I saw Tom’s interactions motivated by the constant desire to point to what he saw as the central theme of scripture and to make it foremost in telling the story of the heritage of the Churches of Christ—when it was evident and when it was obscured and distorted.

The stories of his religious experiences growing up in Missouri, seen in the retrospect of almost eighty-seven years, in his short 2016 memoir Missouri Memories, again reflect Tom’s deep love for his heritage. In the Afterword to the book, Missouri historian Brooks Blevins remarks that “lots of other people with similar upbringings failed to achieve the successes that Tom has achieved and failed to impact the world around them as Tom has done. So some of his story simply illustrates the ability of an extraordinary soul to make the most of what he has at hand, to take from the world that which is enriching, to extract value from the lessons others ignore.”14

To me, Tom’s real significance lay not so much in the in-depth studies he might have made in church history, theology or biblical studies, though he did produce key works—again, especially in my opinion his work on Old Testament and New Testament theology focusing on the love of God. Tom’s real significance was that he himself became a key figure in making the history of the movement, of Churches of Christ, through his teaching and leadership at ACU and Pepperdine, through his efforts at creating this Christian Scholars Conference, by his serving as an elder at the Minter Lane Church of Christ where I now serve, and University Church of Christ in Malibu.

He was part of practically every major event and institution in Churches of Christ from the 1960s until his death. He was instrumental in the formation of Restoration Quarterly and Mission. In the first ten years of Restoration Quarterly, Tom was among the most frequent contributors, and continued to contribute to that journal as well as Image, the Stone-Campbell Journal, Leaven, and many others. He was a frequent presenter at the ACU and Pepperdine Lectures on a wide range of themes geared to inform and build up the church. He was a planner and writer of literature for the Church of Christ display at the 1964 New York World’s Fair; briefly professor at Harding, and long-time professor and administrator at ACU and Pepperdine; founder of the Christian Scholars’ Conference; supporter of the Restoration Theological Research Fellowship, and on it goes.

I was never in a university class that Tom Olbricht taught, but he was my teacher. I was never a colleague of Tom’s on a university faculty, but he was my colleague in countless ways. I was never in a formal mentoring relationship with Tom, but he was and continues to be my mentor.

And I heard a voice from heaven saying, “Write this: Blessed are the dead who from now on die in the Lord.” “Yes,” says the Spirit, “they will rest from their labors, for their deeds follow them.” (Rev 14:13)

- Thomas H. Olbricht, “Understanding the Church of the Second Century: American Research and Teaching 1890–1940,” in Texts and Testaments: Critical Essays on the Bible and Early Church Fathers, ed. W. Eugene March (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1980), 242 (237–61).

- Olbricht, “Understanding the Church of the Second Century,” 248.

- Thomas H. Olbricht, Hearing God’s Voice: Reflections on My Life in the Kingdom and the Academy (Eugene, Ore.: Wipf & Stock, 2012); Thomas H. Olbricht, Missouri Memories (1934–1947) (Eugene, Ore.: Resource Publications, 2016).

- Thomas H. Olbricht, He Loves Forever: The Message of the Old Testament (Austin, Tex.: Sweet, 1980); Thomas H. Olbricht, His Love Compels: The Sacrificial Message of God from the New Testament (Joplin, Mo.: College Press, 2000).

- Hans Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht as Theologian,” Restoration Quarterly 46 (January 2004): 242.

- Olbricht, Hearing God’s Voice, 346–47

- Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht as Theologian,” 244.

- Carl R. Holladay, “Thomas H. Olbricht (1929–2020): A Memorial Essay,” in Rhetoric and Scripture: Collected Essays of Thomas H. Olbricht, ed. Lauri Thurén (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2021), xxxii (xv–xxxvi).

- Holladay, “Memorial Essay,” xxxiii.

- David Baird, “Review of The History of the Restoration Movement in Illinois in the 19th Century, by James L. McMillian and Thomas H. Olbricht (Los Angeles: Sulis Academic, 2019),” Restoration Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2021): 54–55.

- Douglas A. Foster, et al., eds., Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 2004).

- Conference on Scholarship in Churches of Christ (Panel), November 22, 2003, Digital Commons @ACU, Stone-Campbell Audio and Video, https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_audio_video/12/

- Conference on Scholarship in Churches of Christ (Panel), November 22, 2003, Digital Commons @ACU, Stone-Campbell Audio and Video, https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_audio_video/12/

- Brooks Blevins, “Afterword,” in Olbricht, Missouri Memories, 136.