Thomas H. Olbricht: A Memorial Tribute

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: Biblical Scholarship, In Memoriam

Discipline: Religious Studies

I met Tom Olbricht in 1969 when I enrolled in the first of many courses that I took with him as a student at what is now Abilene Christian University (ACU). When Tom died on August 21, 2020, I had been privileged to know him for 51 of the 90 years of his extraordinary life. As I set out to write this memorial tribute, I quickly realized that I could not discuss him and his work as a biblical scholar, especially the teaching and scholarship of the younger Tom Olbricht, except by being partly autobiographical. The following comments are thus not only partly autobiographical but also unabashedly so. A principal reason for my use of this genre is that Tom himself fully embraced autobiography as a form of scholarship.

His first major discussion of his own intellectual and spiritual odyssey was his 1996 work Hearing God’s Voice: My Life with Scripture in the Churches of Christ. That was followed in 2012 by his Reflections on My Life in the Kingdom and the Academy, and in 2016 by his Missouri Memories, 1934–1947. In addition to his own autobiographical writings, he encouraged others to do the same. In 2019 Tom and Gayle Crowe co-edited a volume in which 15 members of the Churches of Christ wrote short autobiographical pieces in which they surveyed their past as members of the Stone-Campbell movement and offered musings on its future as an ecclesiological entity.1 Along with the autobiographical, there was also the biographical, seen for instance in the 2018 volume that he co-edited on his friend Gail Hopkins, which included a number of contributions in which various individuals, including Tom, shared their memories of Gail’s fascinating life as a baseball player, medical doctor, and traveling companion of Tom and Dorothy Olbricht.2

In emphasizing autobiography as a form of scholarship, Tom was not breaking new ground, but fully exploiting a genre first introduced into Christian theology by Augustine, whose Confessions was the first spiritual autobiography in the history of Christianity. And yet, as students of Augustine are well aware, that Christian classic is not pure autobiography. Books 1–9 are indeed fully autobiographical, but Book 10 is on epistemology (including memory), and Books 11–13 are exegetical, focusing on Genesis 1. In a similar way, Tom’s autobiographical writings are not simply autobiographical but involve Scripture, theology, rhetoric, and history. Nor are they ever an end in and of themselves, but rather a heuristic means of seeking to understand our individual and collective past so that, with sharpened self-understanding, we might serve God, the church, and the academy more effectively in the present and the future.

In his 2004 treatment of Olbricht in Restoration Quarterly, Hans Rollmann placed all of Tom’s various and particular scholarly activities under the broad rubric of theology but emphasized that Tom was first and foremost a biblical theologian.3 That was indeed my first impression of Tom. He arrived at ACU in 1967 with 10 years of teaching experience under his belt, one at Harding (1954–1955), four at Dubuque (1955–1959), and five at Penn State (1962–1967), all spent teaching courses in rhetoric, speech, and communication. To come to Abilene, therefore, marked a major professional change, for here he was not a teacher of rhetoric but rather a Bible teacher and member of what was at that time the Bible Department. From the very beginning he was a Professor of Biblical Theology, and that was what he did for the 20 years (1967–1986) that he spent at Abilene, especially in those early years.

What had specifically prepared him for this new phase of his professional life were the three years he had spent at Harvard Divinity School, earning his Bachelor of Sacred Theology degree from 1959 to 1962. There he was especially influenced by the work of G. Ernest Wright, who had joined the Harvard faculty in 1958, just one year before Tom matriculated there as a student. But Wright was already well known for a book that was published in 1952, God Who Acts: Biblical Theology as Recital, and the title of the memorial volume for Wright recalled that part of his work: Magnalia Dei: The Mighty Acts of God. As for New Testament at Harvard, it was especially Krister Stendahl who gave emphasis to biblical theology. Stendahl’s classic article on “Contemporary Biblical Theology” was published in 1962 in volume one of The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible. It was biblical theology as conceived and studied at Harvard in the late 1950s and early 1960s that Tom Olbricht brought with him to Abilene in 1967, and those are the courses that I took with him and most remember from him.

To state the matter differently and as starkly as possible, it was not rhetoric, rhetorical criticism, and the rhetorical analysis of Scripture that Tom taught at ACU and emphasized in his early years there. On the contrary, it was biblical theology. It was only after Tom had left Abilene and moved to Pepperdine that he returned to his “first love” and began to organize conferences on the rhetorical interpretation of the Bible. There were some seven such Pepperdine conferences that took place between 1992 and 2002, with Stanley Porter and Vernon Robbins among his major dialogue partners.

In what remains of this paper, I shall imitate Tom and take the autobiographical route by recalling some of the interactions that stand out in my mind and memory. The first concerns Tom as a teacher. From the very first time that I heard him speak in his quite distinctive style of lecturing, I knew that he was brilliant. What I did not initially appreciate was his extraordinary range of interests and his remarkable erudition in so many areas of research. To this day, I cannot use the word “polymath” without thinking of Tom. I especially benefited from his biblical courses, particularly those on Old Testament Theology. Indeed, I took all of my advanced courses on Old Testament at ACU with Tom—John Willis arrived at ACU only after I had finished my coursework—and so it was he who laid the foundation in Old Testament Theology (particularly Gerhard von Rad) on which others built. In New Testament I benefited enormously from J. W. Roberts, but I wrote my master’s thesis under Tom’s direction. Given Tom’s theological emphasis, the thesis was appropriately on “Abraham in the Theology of Paul and Luke.” I have no idea how many theses Tom directed over the years at ACU and Pepperdine, but I am proud to say that I was among his first graduate students in Bible to write under his direction.

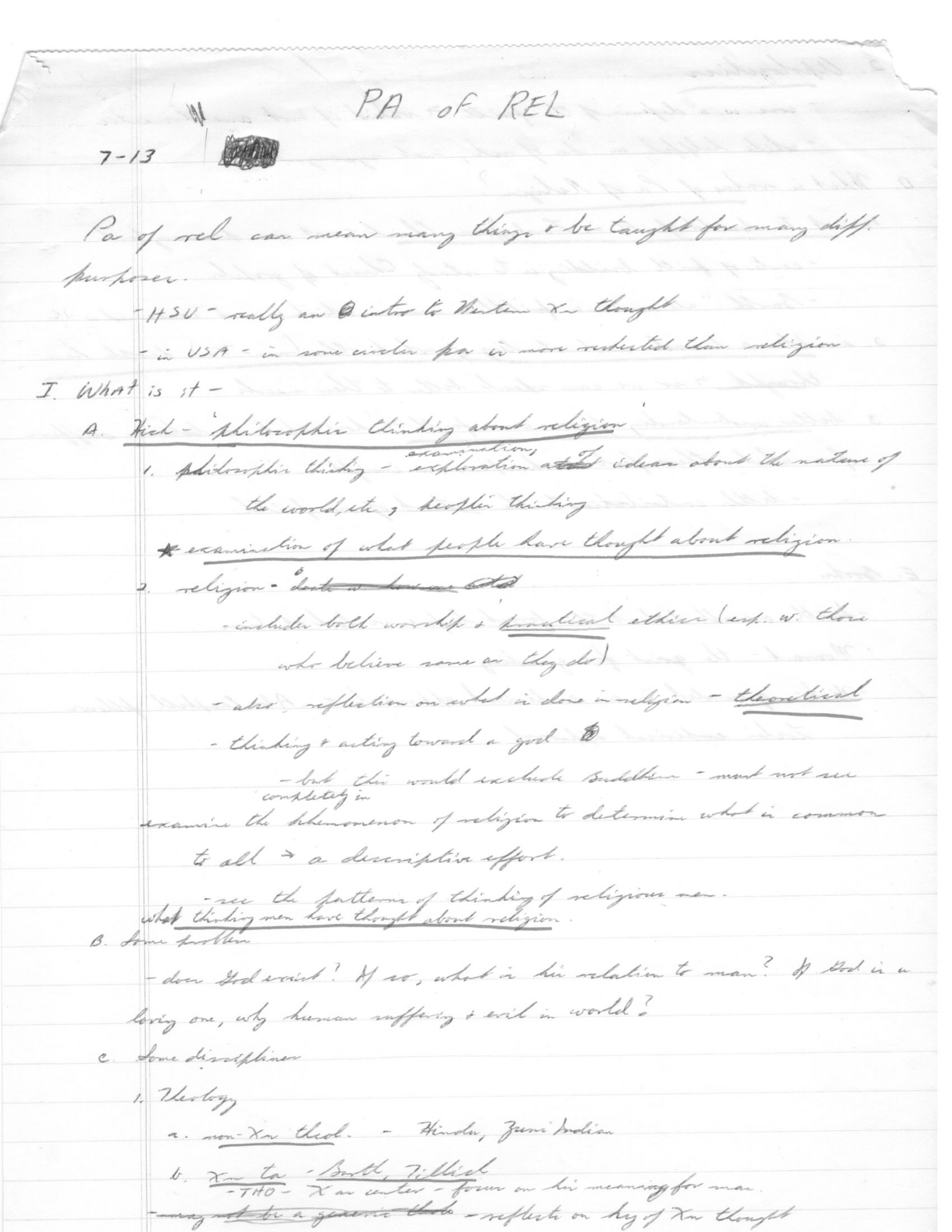

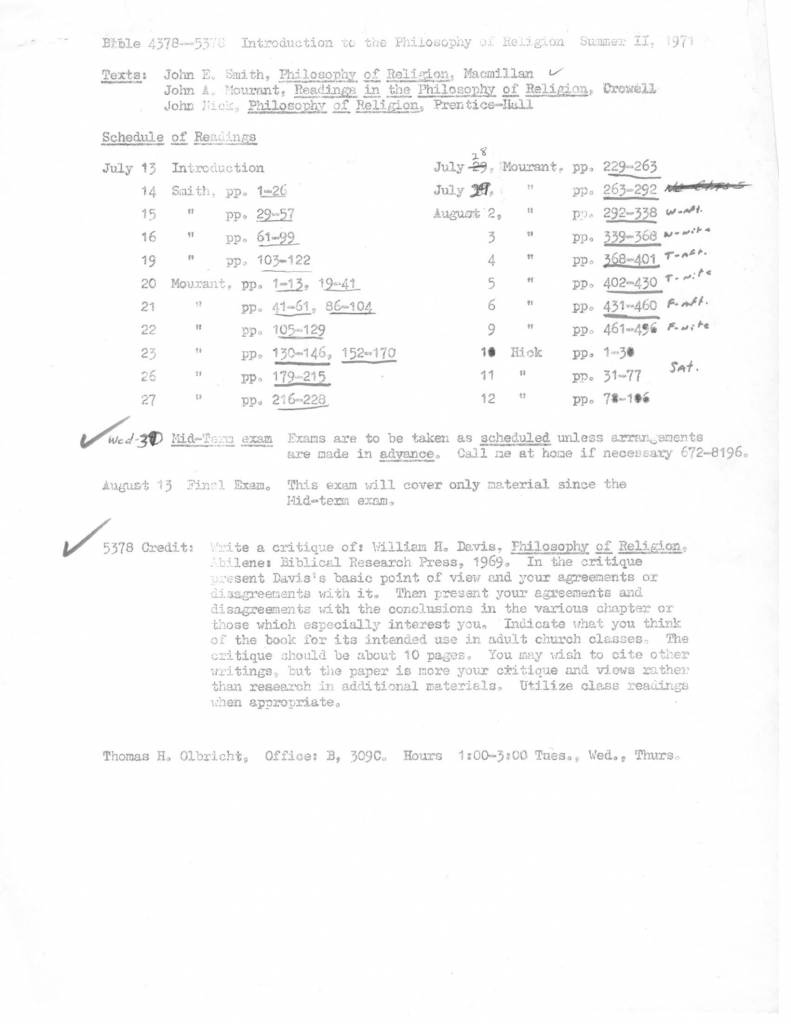

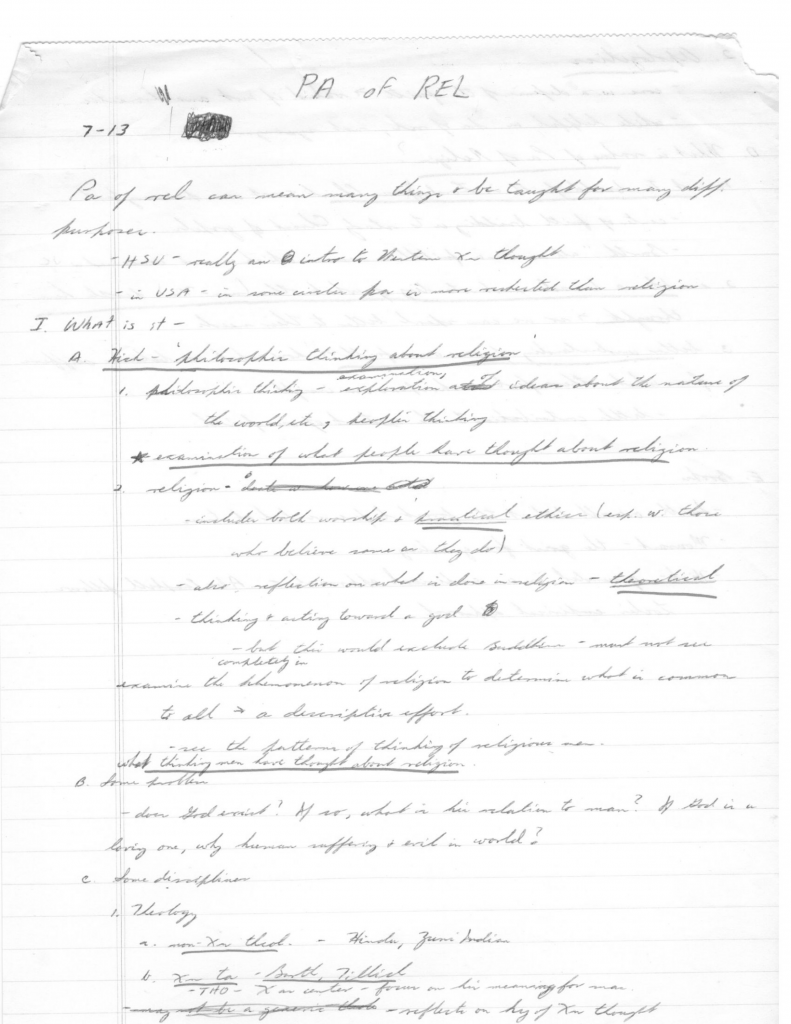

New Testament, however, was not the only subject that Tom taught at Abilene in those early years. Among other subjects, he taught a Philosophy of Religion course. Although I learned a lot in that course, I confess that it was not one of my favorites. At its conclusion, I dutifully put my notes in a folder and filed them away, assuming that it would be quite some time before I would have need for them again. I could not have been more wrong in making that assumption. Late one night about a year or so later, my phone rang and it was Tom. He explained that he needed to have emergency back surgery and would not be able to teach his courses for the next four to six weeks. The college had been able to persuade faculty members to take over all of his courses for this time period, except for one course, namely, the one on Philosophy of Religion. No one was either willing or able to teach it, so he had decided to ask me to do it. Making use of rhetoric as the art of persuasion, he expressed his confidence in my ability to do a good job, and I reluctantly agreed to do so, thinking—knowing—that I really had no choice but to say yes. Suffice it to say, I did not do a great job, but I did do the best job that I could under the circumstances. So, it is to Tom Olbricht that I owe my initiation into the realm of teaching a course. In later years, I came to suspect that Tom decided to ask me, not simply out of desperation or because he really thought that I knew enough to teach the course. No, it was because he knew that I had only scratched the surface of the topic when I was a student and that I needed to learn more. And there is no better way to learn a subject than having to teach it to others.

There is one other aspect of academia to which the young Tom Olbricht introduced me, and that was the practice of hospitality. I had been a guest in the homes of other Abilene faculty members as an undergraduate, especially that of LeMoine Lewis, and Tony Ash once invited me to his house at an end-of-the-year function when I was his teaching assistant. But Tom and Dorothy Olbricht were the first to invite my wife Karol and me as graduate students to their house to share a meal and to meet their family. Hospitality is an essential aspect of the mentoring process, and I am delighted that the new Randolph Mentoring Program of the CSC is making the practice of hospitality one of its foundational principles.

I close by briefly mentioning seven different ways in which Tom sought to connect with me in the post-thesis years. First, after I finished at Abilene, he was among those mentors who sent me to Yale and to Abe and Phyllis Malherbe. In short, he did what he could to help provide me with a new mentor and taskmaster for the next stage of my academic journey. And for the next decade or so, during my Yale years and my early years in Miami as well as his later years at ACU, there was very little contact between us. That began to change after he moved to Pepperdine.

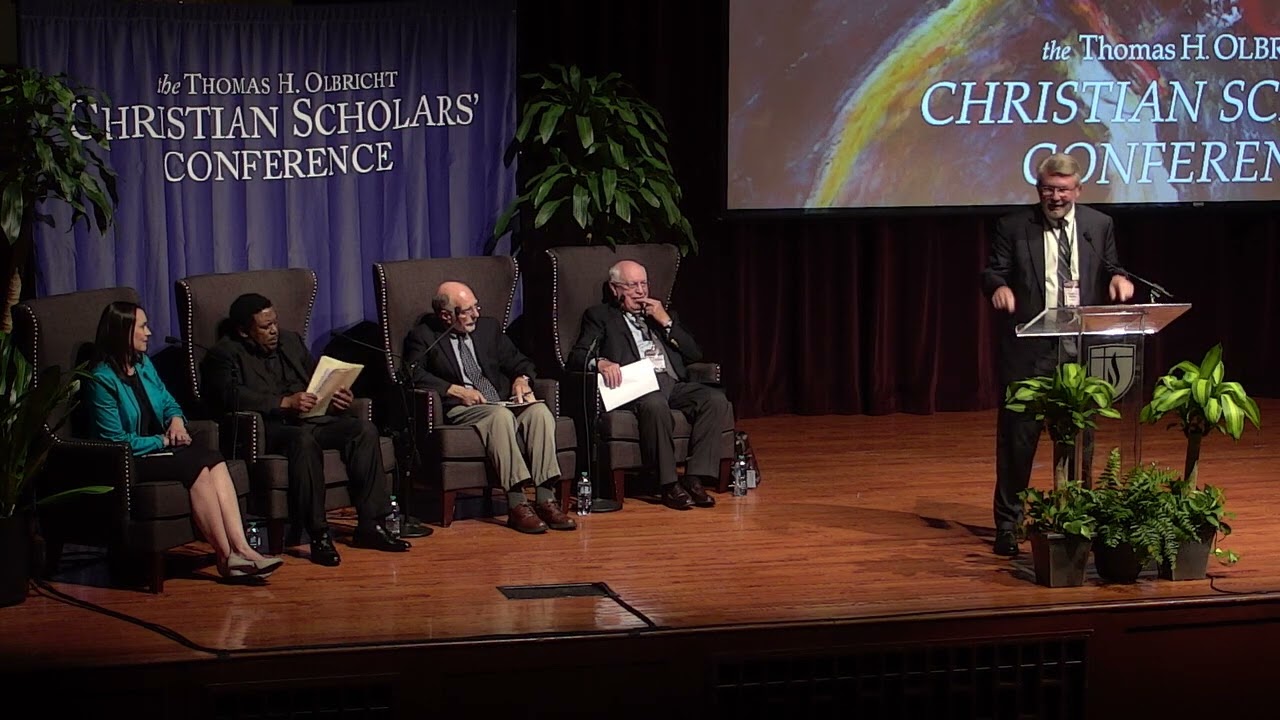

Consequently, the second thing he did was to reach out to me in the late 1980s and invite me to give a paper at the Christian Scholars’ Conference. So, it was Tom, after whom this conference is now so fittingly named, who was responsible for me first presenting a paper at the CSC. The third thing he did was to invite me to give a paper at one of the Pepperdine’s Rhetorical Analysis of Scripture conferences. Through that initiative he sought to bring me into the rapidly expanding world of the rhetorical criticism of Scripture, which I was more than happy to join. That was my first entrée into that world, which, from the perspective of most members of the New Testament guild, was Tom’s greatest and most lasting contribution to biblical studies.

The fourth thing that Tom did was to ask me not only to read his work but also to criticize it. Tom’s emails to me over the years were often periodic—like the proverbial Son of Man, you never knew when they would arrive. When one of these arrived requesting feedback on his work, he paid me what I consider one of the highest compliments he ever gave me. He said, “I am sending this to you because I know you will not hold back in taking me to task or in criticizing parts of the argument that are weak.” In short, one of the goals of a good teacher is to train her or his students so that they can become full conversation partners on scholarly matters. Tom understood that and enlisted my participation in his ongoing work.

The fifth thing he did was to take the initiative in organizing collaborative efforts that culminate in important publications. It should come as no surprise, therefore, when I say that the second Festschrift in honor of Abe Malherbe was Tom’s idea. L. Michael White and I may have done the lion’s share of the work on Early Christianity and Classical Culture: Comparative Studies in Honor of Abraham J. Malherbe (2003), but the volume itself was Tom’s brainchild.

The sixth thing he did was to maintain contact at the personal level as well as the professional one, and to introduce me to members of his social network whom I did not know. So, on one of the trips that the Olbrichts and the Hopkinses took together, they came to South Florida, where they met not only with Karol and me but also with Dave and Linda Graf, old friends of the Hopkinses. Dave was my colleague at Miami and is one of the world’s leading experts on the Nabataeans, so it was a pleasant and mutually beneficial meeting for all of us.

Finally, in the last few years of his life he involved me in one of his many projects and one that I had not fully appreciated until I received his invitation. This was his work on interpretation of the Bible in North America. To make a long story short, I am slowly preparing a volume of Tom’s essays on this topic, which has already been accepted by SBL Press for publication in its History of Biblical Scholarship in North America series. Organizing and editing the essays has proved to be far more challenging than I had anticipated, but the current plan is to have the collection open with Tom’s essay on histories of American biblical scholarship. Next will come two major sections. The first will be on biblical interpretation in North America from the beginning through the end of the nineteenth century, and the second on twentieth-century North American biblical interpretation. Each of these two major sections will begin with a historiographical overview, followed by studies of individual scholars. For example, in the first section the overview will be followed by studies devoted to such interpreters as John Cotton, Alexander Campbell, and Charles Hodge. In the second part, devoted to the twentieth century, Tom’s survey will be followed by studies of such interpreters as Kirsopp Lake and some of the so-called schools of interpretation, including the Albright School and the Chicago School. There will be a final section devoted to more synthetic and synchronic pieces not easily separated into either the nineteenth or twentieth century, such as Tom’s article on the study of Isaiah at Princeton Theological Seminary in which he compares and contrasts Joseph Addison Alexander and Jimmy Roberts as interpreters of the book of Isaiah.

What this final project does is to remind all of us that Tom as a biblical theologian was acutely aware that such work involves entering a conversation about Scripture that has been ongoing for centuries and is always conditioned by the time and place of the interpreter. Tom saw his work on the history of biblical interpretation as part and parcel of his contribution to biblical interpretation itself, and we are all the richer for it. I look forward to sharing this final gift of Tom’s scholarship with readers everywhere.

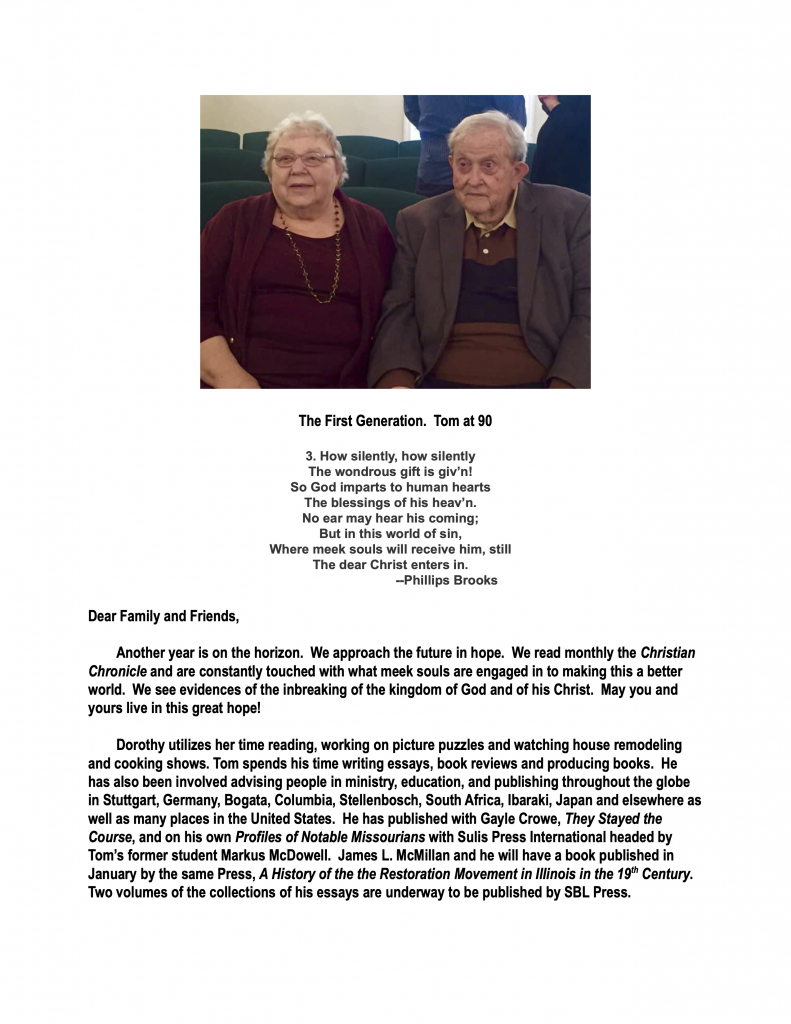

One way Olbricht kept in touch was by sending his annual Christmas letter. Olbricht sent this Christmas letter in 2019.

- Thomas H. Olbricht and Gayle M. Crowe, Staying the Course: Fifteen Leaders Survey Their Past and Envision the Future of Churches of Christ (Los Angeles: Keledei, 2019).

- Leah G. Hopkins and Thomas H. Olbricht, eds., Bat, Scalpel, Sheepskin, Beneath the Cross: Narratives on the Life of Gail Eason Hopkins (Nashville: Elm Hill, 2018).

- Hans Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht As Theologian,” Restoration Quarterly 46, no. 3–4 (2004): 235–48.