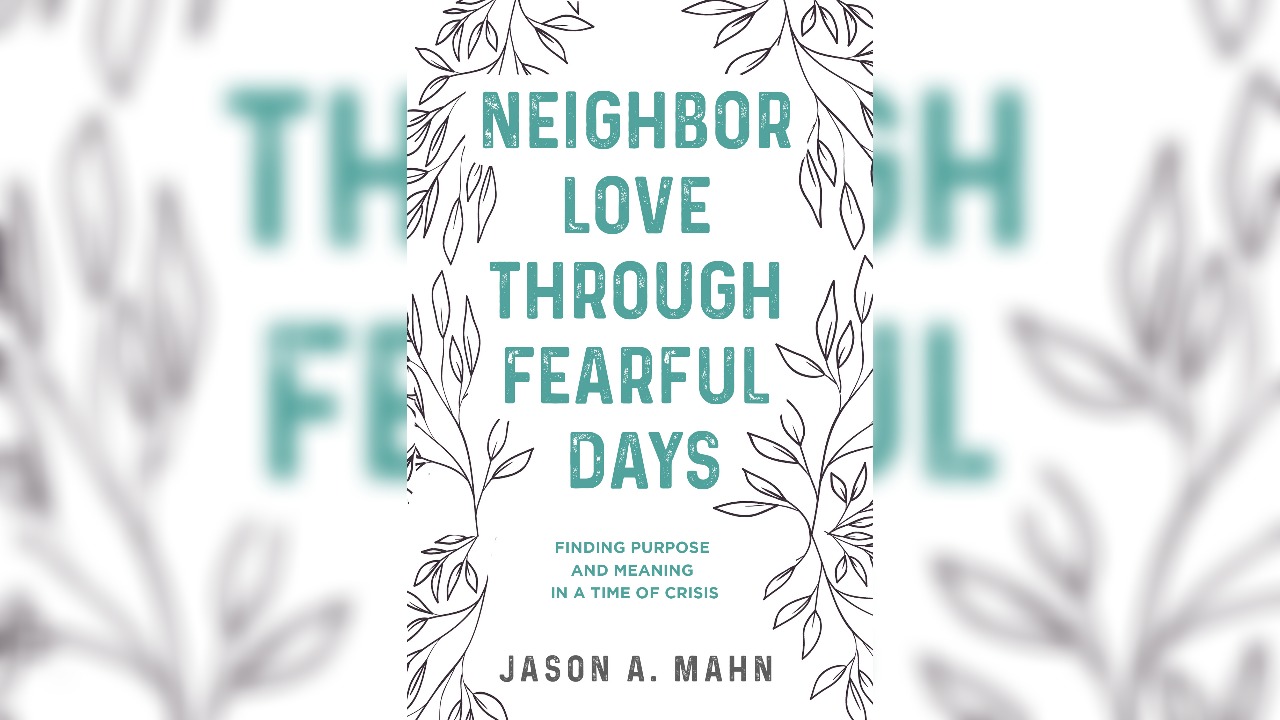

Review of Jason Mahn, Neighbor Love through Fearful Days: Finding Purpose and Meaning in a Time of Crisis

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: Suffering and Death, Vocation

Discipline: Religious Studies, Theology

If a sacrament is something ordinary that becomes a vehicle of grace—something like water, bread, or wine—then Jason Mahn has written a deeply sacramental book.

Begun as a daily journal during six of the darkest months of 2020, this is a book of stories—stories that chronicle ordinary acts of courage, of neighbor helping neighbor, of students probing the weighty issues of life, of survival in the face of crisis. The grace that shines through these ordinary, everyday stories is what makes them sacramental.

Mahn then does something that is sacramental in its own right. He connects our smaller, quotidian stories to the larger stories that define our time. For the most part, those larger stories are tragic stories—devastating stories of disease and death, of fires and floods and injustice based on race and social standing.

We even find grace in Mahn’s admission that “I am writing these daily entries because I am scared—scared . . . for how I will respond to this pandemic [and] what will become of me, morally and spiritually, and what will become of my Christian calling to love and serve the neighbor.”

Mahn seems to ask, What might the ordinary stories of my life finally mean in light of these larger, tragic stories that engulf us all? How might I connect my ordinary stories to the suffering that swirls around me and pervades our time? And how might I do so in ways that embody the radical love to which all Christians are called?

In the end, this is a book on vocation—hearing the call, the summons, to something larger and more compelling than self and self-interest. And Mahn helps us to grasp that summons by exploring the potential connection between our ordinary stories and the three great crises of our time—(1) the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) the pandemic of racial hatred, and (3) the devastating reality of climate change. Each of these larger stories are stories of untold suffering, but precisely for that reason, Mahn insists that these are the stories that call us into lives of meaningful vocation.

Even as he explores each of these crises in detail, Mahn wants his readers to understand that these three crises are deeply interconnected and essentially form a tangled web. “Digging at one root,” he writes, “will find others interconnected, like the shared root system of aspen groves.” And then, in perhaps the most important passage in the book, he writes this:

Treating a virus in isolation from the systemic injustices that make some more vulnerable than others, or treating the domination of people of color or women as though it were unrelated to the domination of nonhuman nature, or even trying to solve climate change while ignoring habitat and topsoil loss and the erosion of sustainable rural communities—all these fail to get at the root of the problem. That root is the human heart, a heart turned in on itself, a heart that craves freedom from suffering at any price, even by magnifying the suffering of others. (pp. 155–56)

Meaningful vocation emerges, Mahn claims, when we abandon the assumption that freedom from suffering is a human right and freely share in the suffering of others. In this prescription, Mahn lifts up the New Testament image of the kingdom of God, a kingdom in which we go forward by repenting and turning back, in which we live by dying to self, and in which the first are last and the last are first. In this context, he cites the theologian Kelly Brown Douglas who observes that Jesus “departs the space of the privileged class” and “fully divests himself of all pretensions to power, privilege, and exceptionalism.”

In other words, we will never discover meaningful vocation when we seek to escape the crises of our time and return to more normal days. Rather, we discover meaningful vocation when we embrace the crises of our time. And we embrace those crises when we stand in solidarity with those who suffer from those crises the most.

Indeed, there is no other way out. We will save the planet when we abandon our presumed right to exploit it. We will save humanity when we no longer seek to save ourselves at the expense of those others we imagine are not as deserving as ourselves. And while we may never fully defeat COVID, we will achieve some measure of victory only when we relinquish our claim to freedom at the expense of the health of our neighbors.

Mahn therefore contends that the single most important question of our time is “whether and how people can find solidarity in shared suffering.” And while that is the single most important question of our time, Mahn also contends that this is the single indispensable question for hearing the voice of vocation.

Grounded in the ordinariness of our lives, the crises of our time, and what Luther called “the theology of the cross”—the theology that defines the Christian faith—this book is a cornucopia of insight and wisdom, the sort of wisdom that, if we are open, can finally save us from ourselves in this dark and foreboding time.