“Church Doctor” Thomas H. Olbricht: Impressions and Sentiments of a Former Student

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: In Memoriam

Discipline: American Religious History

When Professor Hans Rollmann delivered one of the six papers at the American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature (AAR/SBL) in 2003, recognizing the scholarship in the Churches of Christ from the previous fifty years, his focus was on “Tom Olbricht as Theologian.”1 Rollman closed his paper by suggesting that because of Olbricht’s extensive influence he merited the church catholic title “Doctor of the Church.”2 I am grateful to have learned from the great “Church Doctor” in the Churches of Christ. Tom Olbricht was my professor, M.A. advisor, mentor, colleague, and friend.

Olbricht’s scholarship, preaching, and teaching were always done with an eye toward the church because for Olbricht, his work was always for the “church’s sake.” That devotion was inspiring. He was instrumental in shifting Church of Christ hermeneutics away from legalism and toward a biblical theology that embraced both the Old and New Testaments. Rollman notes, “He is able to establish an inner connection between biblical facts and the narrative in which they are embedded, thus overcoming the detached, isolated biblicism of the command-and-inference theologians.”3

For Olbricht, the biblical center for theology was the “mighty loving acts of God,” and the culmination of those acts was Jesus, and his death, burial, and resurrection.4 As a historian of the Restoration Movement Olbricht was aware that our postmodern era was an age of pluralism; thus, what had worked in the modern era for the Restorationists in America might not continue to work. Alexander Campbell and Walter Scott’s emphasis on Jesus as the “lawgiver” led the church to say little about the earthly Jesus. Consequently, the priority became ecclesiology rather than Christology.5 In a 1992 article in Leaven, Olbricht attributes this way of thinking to the early Restorationists’ emphasis on the Scottish Enlightenment, which focused on external reality and external structures, and expressed concern that “the universalistic aspirations of the Enlightenment might not survive.”6 Olbricht was right. We continue to struggle today. He noted that the church was already moving away from the monarchical-legal blueprint to the family blueprint, and this was good. He noted that already, “The elders and other leaders of the church have become more parental types who serve as models for life, rather than as skilled blueprint readers.”7 Olbricht did not fear reexamining the ideas and principles of the Restoration Movement. In the parenting model “The church is enclosed in a structure but is not a structure. It is a body of living, breathing people, loving one another because Christ loved them first.”8 The pressing ecclesiological question for Olbricht was how to adjust in the postmodern era to keep biblical theology (and thereby the church) relevant. Olbricht’s “church” was a large one. He networked among all the Christian colleges, para-church organizations, professional organizations, and hundreds of congregations. His networking included local churches throughout the United States and in many foreign countries, and he seemed to remember everyone he met.

In Olbricht’s book Reflections on My Life: In the Kingdom and the Academy he says that about 120 of his students taught or still teach in universities.9 Olbricht’s list included my classmate and friend Pat Graham, emeritus director of Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology, at Emory University. When I asked Pat to submit his reflections about Olbricht, he was concise and accurate:

. . . Tom’s lectures were interesting and sprinkled with good humor; he always read students’ papers carefully and noted areas for improvement; and he was always attentive to how the subject matter could have an impact on the church. Tom always demonstrated a kind spirit, was genuinely concerned for the health of the church, and intellectually curious. . . It was also delightful to run across someone outside the Churches of Christ circuit, who had worked with Tom on a research project and typically had lavish praise for his work.10

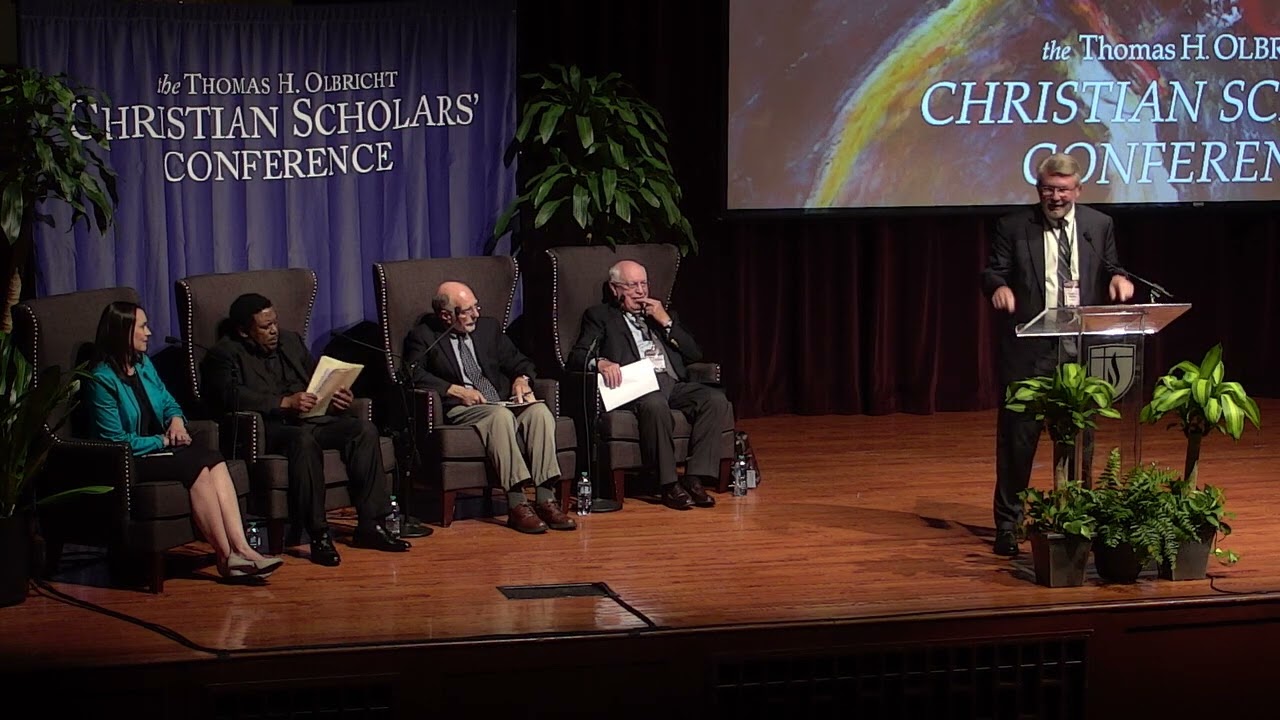

Yes, that is the Tom Olbricht I knew. He was a mentor for life for his students. We are here today because along with his involvement in the AAR-SBL meetings, he had the idea of a Christian Scholars’ Conference to serve the church’s scholarship as well as the church’s leaders. He and Dorothy extended generous hospitality. His breadth of scholarship is illustrated by his prolific writings. Without doubt he was a renaissance man and always a servant of God working in and for God’s kingdom.

One story that has yet to be told is how Olbricht influenced the world for women studying theology and religion. I seek to provide some glimpses into the intersections of Olbricht’s scholarly story with my own, from the tumultuous mid-1970s until his death—a span of forty-six years.

I believe I was the only female graduate student in biblical and theological studies at ACU in 1974. I am certain that I was the only woman in Olbricht’s Masters in Doctrines program. The students were smart young men, and several would jokingly ask me, “Why are you here?” My short answer was, “I’m not sure.” My longer answer started with, “It’s complicated.”

In the fall of 1974, scholars like Mary Daly and Elizabeth Schussler Fiorenza were writing classic works that continue to influence feminist and theological studies. In our tradition, those women were not known, and the very word “feminist” was not viewed positively. In professional tennis, three-time Wimbledon winner Billie Jean King could not get her own credit card because she was a woman.11 Increasing numbers of women were going into the workforce and moving into careers that had previously been occupied by men. Increasingly mainline denominations began to ordain women. In a few Churches of Christ, women’s roles were being discussed. In 1975, Bobbie Lee Holley became the first female editor of Mission Journal, another indication that not only society but also the Churches of Christ were beginning to change.

Olbricht never asked me, “Why are you here?” In the fall of 1974, our first class together was “Introduction to Doctrines.” He started that seminar with introductions. When he introduced me, he told a small portion of his story about growing up in Thayer, Missouri, in his beloved Ozarks, and then he mentioned that my family was from that area: Mammoth Spring, Arkansas. It was a small detail but an important one, because it made me feel “in.” Clearly, Olbricht loved his Ozarks heritage and for me to be Ozarkian and Church of Christ increased my status a hundredfold, or at least it seemed so to me.

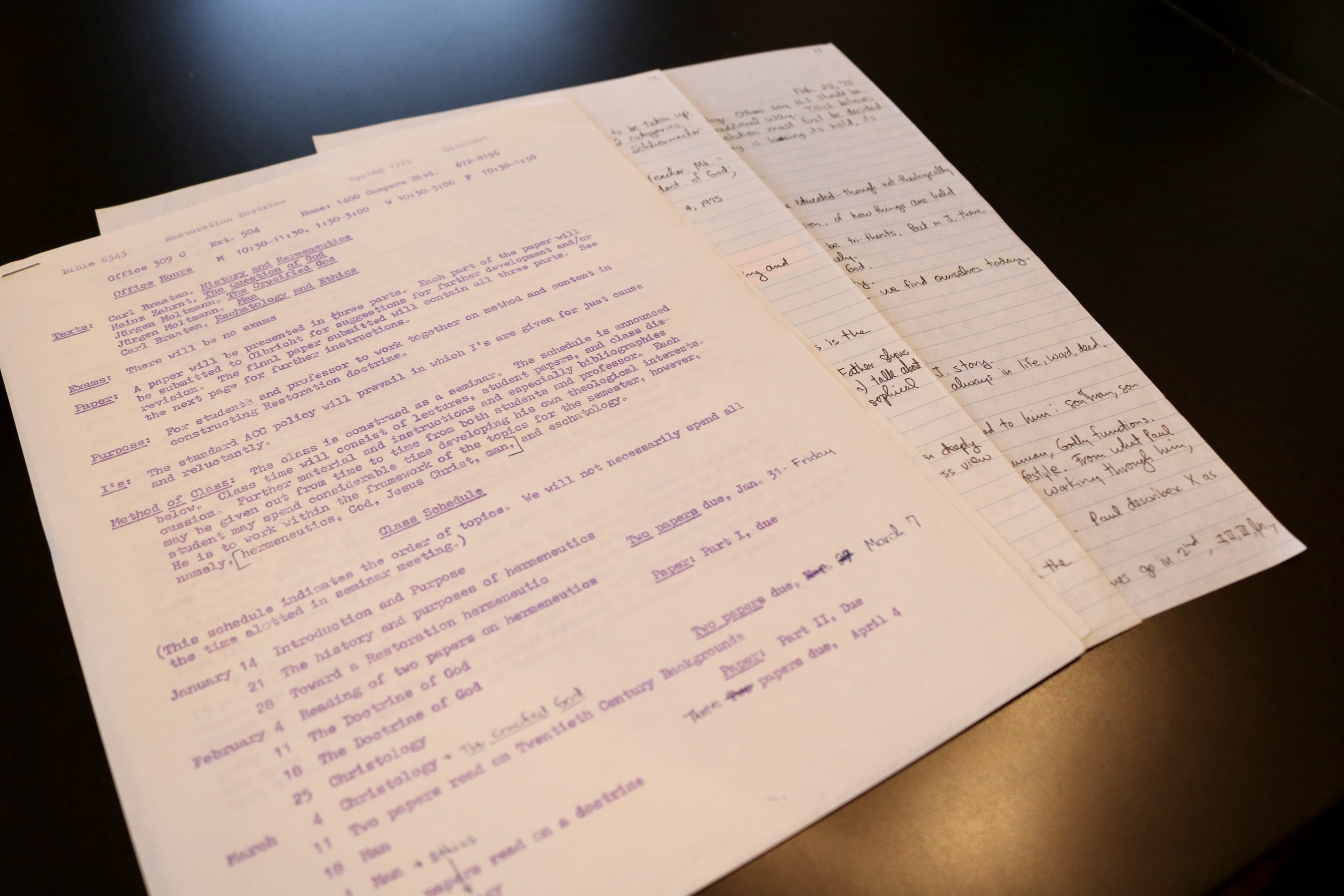

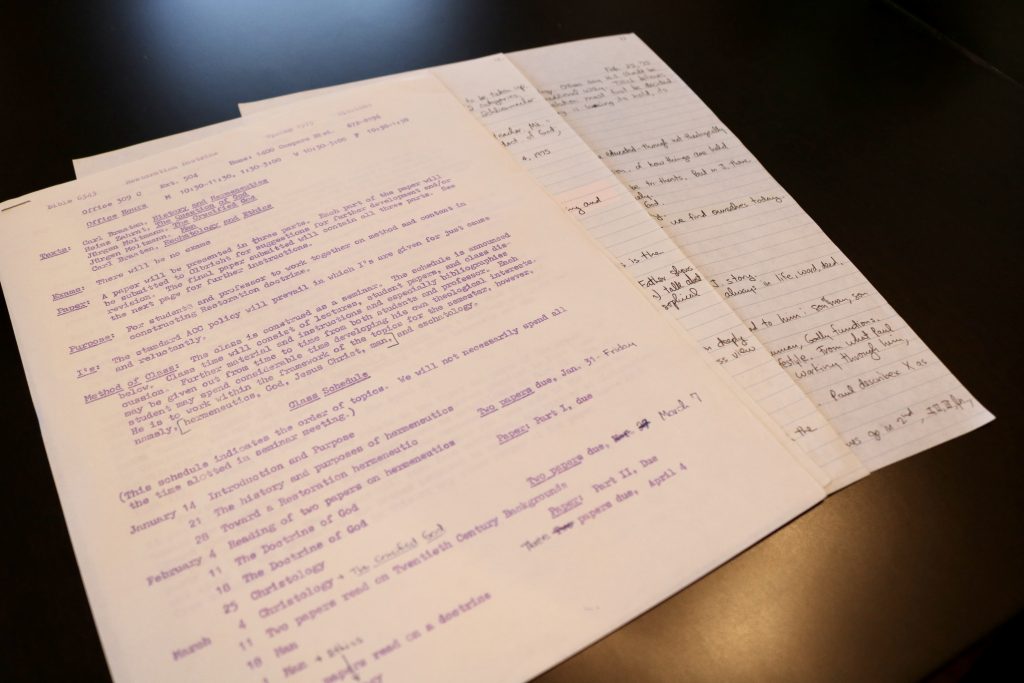

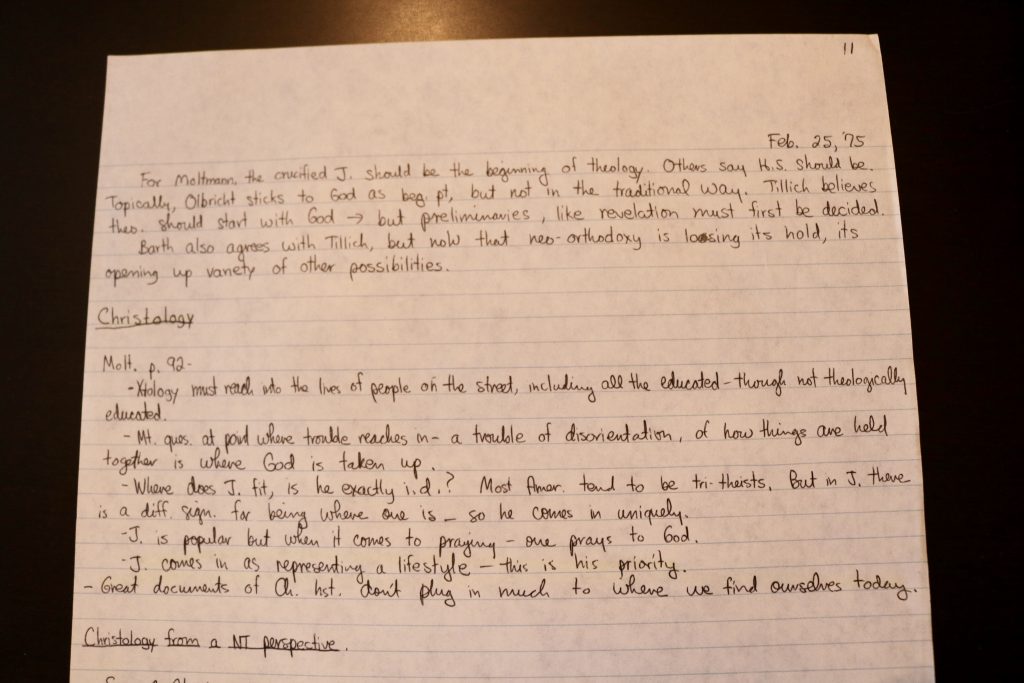

When I was invited to write this paper, I began by looking back over my class notes. I took four classes with Olbricht, and I have a complete set of detailed notes from each one. The first class, “Introduction to Doctrines,” was organized around the standard topics for an introductory class: God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, the Church, and others.

I was particularly interested in Christology. Rollmann speaks of Olbricht’s biblical theology as being centered in Jesus of Nazareth, who is “the ‘culmination of God’s mighty acts’ as found in Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection.”12 Rollman goes on to say that from Olbricht’s understanding of hermeneutics, ethical imperatives were never prior to, but always followed from, God’s actions in Christ; thus, human ethical actions are “replications of the actions of God through Christ.”13 In his own words, Olbricht said, “We only interpret aright the commands of Christ when we are aware of the manner in which they replicate Christ’s own actions.”14

This “big idea” of New Testament theology centering around Jesus of Nazareth, who is the culmination of God’s Mighty Acts, was the focal point of Olbricht’s Christology as presented in the class. Particularly Mark’s gospel spoke to this set of issues. In 1979, Olbricht published The Power to Be: The Lifestyle of Jesus from Mark’s Gospel. This book was clearly intended to serve the church. In fact, a teaching manual was available through religious bookstores. When the book was revised and published again in 2003, discussion questions were included at the end of each chapter. Also, in his 2003 revised version, Olbricht added a section that placed the Christian religion on the side of supporting human rights and supporting all who were oppressed. Several biblical examples of Jesus’ treatment of women were included in this chapter, including the “aggressive faith” of the woman who had been hemorrhaging for twelve years (Mk 5:27–30).15 In Mark’s gospel it was Jesus’ “actions” toward the women that were to be replicated or followed, not ethical imperatives. The stories in Mark did not contain stated ethical imperatives.

The first edition of The Power to Be was written in the American context of “The Jesus Movement,” a countercultural response to the Death of God movement in the late 1960s. There was popular interest in a Jesus who was relevant and who pointed the way, and the index finger up, was their symbol. Although it grew quickly, it was declining by the early 1980s. Despite the decline of the movement itself, its influence carried on. The message of Jesus as the Way, continued to be incorporated into conservative religious culture. This can be seen through the emergence of new denominations, para-church organizations, and contemporary Christian music.

Olbricht’s work outside the formal classroom was intergenerational as well as transcultural, as he would speak, preach, and teach to various churches and other groups throughout the world. As far as his own evaluation of his perspectives and how he reached the conclusions he did, he said,

. . . My perspectives were not developed solely in the classroom. They emerged in the crucible of specific Churches of Christ across the United States and other regions of the world. They were not ivory tower events, nor intended for academic consumption only. No theology which has demanded historical respect has ever been isolated from the real-life struggle to be God’s people.16

Back to the mid-1970s: my own formal study of theology with Olbricht continued in the seminar “Restoration Doctrines.” I wrote my paper on Christology. One of the five texts required was the 1974 English translation of Jürgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology, one of the seminal texts of twentieth-century theology. Later I would learn more about liberation theology because of Tom Olbricht.

When I was introduced to Moltmann’s work I was introduced to a whole new way of thinking about Christology, Jesus, and even God. Moltmann put God’s suffering on the cross at the center of the Christian faith.17 Moltmann’s God was the God who suffers with us. This is a God who knows inner and universal suffering by God’s own experience.18 Moltmann and other theologians of this era created new conversations about God and suffering, with bold claims that the problem of evil and suffering cannot be resolved by Greek philosophy, which advocated for a transcendent God who was above suffering. Rather, Moltmann declared, “For a God who is incapable of suffering is a being who cannot be involved. Suffering and injustice do not affect him. And because he is so completely insensitive, he cannot be affected or shaken by anything. He cannot weep, for he has no tears. But the one who cannot suffer cannot love either.”19 I am grateful this book was “required.” Olbricht consistently required his students to read the most current and cutting-edge texts.

A God who suffers alongside humans is a radical construct. Moltmann was one of several German and Latin American theologians who turned to political theology and liberation theology to speak to the suffering and the “vicious circles” of death in this world, which included marginalized groups like the poor and women.20

Dorothee Soelle was a contemporary of Moltmann’s who addressed suffering through political theology. As I explored thesis topics Olbricht suggested I consider Dorothee Soelle, whose writings were just beginning to be published in English. Initially, I read such works as Political Theology and Christ the Representative. Soelle addressed the growing secularization in the West and the need to speak against the suffering of the marginalized and to speak for justice. She focused on a new image of Christ and new ways to imagine Christ representing humanity before God. Soelle made the provocative statement that “In the face of suffering you are either with the victim or the executioner, there is no other option.”21 Clearly, my interest was piqued.

One of several differences between Olbricht’s Christology and that of Moltmann and Soelle was that Olbricht was rooted in the Restoration tradition, which focused on the individual’s relationship to God as the foundation for the church and the foundation for change; whereas, Moltmann and Soelle focused on the systemic issues. However, none of the three ever abandoned the need to speak to the suffering of the world, and the need to free humanity from the suffering. For Olbricht, “The purpose of the death of Jesus was to release men and women enslaved by sin.”22

Olbricht, Moltmann, and Soelle were all engaged in welcoming to the table those who suffered, those who were different, those on the margins—including women. In different hermeneutical ways, using different methods, they all pointed to Jesus and the cross as the model of such “mighty actions.”

My paper only probes the question I raised in the beginning: how did Olbricht influence the world for women studying theology and religion? It does provide an early snapshot from my vantage point as his student and later his colleague and friend. To get the full picture, there is more research to be done. These are my impressions of how Olbricht worked with and for me, one female student, colleague, and church friend, in the context of a society that was undergoing much change, and a church that was resistant to many of the gender role changes.

Olbricht did not laugh about me being enrolled in his M.A. in Doctrines program. What if Olbricht had been humored by my presence? Neither of us could know then that my being in his graduate program might “count” for anything within the academy or church. What if he had not “welcomed me to the table” that first day? What if he had not provided a way for me to pursue topics that were exciting to me? What if he had not encouraged me through the years? In other words, from my vantage point, he “normalized” my presence and my work at ACU, and in some ways, he “normalized” my own work in the academy and church throughout the years. His influence on me was profound, and I am forever grateful. However, this is one story. Other female students and church women benefited from Olbricht’s support both within and outside Christian universities. I look forward to hearing their stories, as well.

- Hans Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht As Theologian,” Restoration Quarterly 46, no. 3–4 (2004): 235–48.

- Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht As Theologian,” 248.

- Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht As Theologian,” 247.

- Rollmann, “Tom Olbricht As Theologian,” 242–43.

- Thomas Olbricht, “A Theology for a New Century,” Leaven 2, no. 3 (July 20, 2012): 7, https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol2/iss3/3.

- Olbricht, “Theology for a New Century,” 4.

- Olbricht, “Theology for a New Century,” 7.

- Olbricht, “Theology for a New Century,” 8.

- Thomas H Olbricht, Reflections on My Life: In the Kingdom and the Academy (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2012), 177.

- M. Patrick Graham (former student of Tom Olbricht, at Abilene Christian University), in email correspondence with the author, February 1, 2021.

- Gail Collins, When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present (New York: Little, Brown, 2009), 250.

- Rollman, “Tom Olbricht as Theologian,” 244.

- Rollman, “Tom Olbricht as Theologian,” 245.

- Olbricht, Hearing God’s Voice: My Life with Scripture in the Churches of Christ (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 1996), 348.

- Thomas H. Olbricht, The Power to Be: The Lifestyle of Jesus from Mark’s Gospel (Abilene, TX: HillCrest, 2003), 87–104.

- Olbricht, Hearing God’s Voice, 336.

- Rachel Muers and Mike Higton, Modern Theology: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2012), 270.

- Duncan Reid, “Identity, Relevance and the Crucified God,” Pacifica 25, no. 3 (October 2012): 272.

- Jürgen Moltmann, The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), 222.

- Moltmann, The Crucified God, 329–38.

- Dorothee Soelle, Suffering (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), 32.

- FOlbricht, The Power to Be, 169.