A Different Direction

Volume 1 | June 6, 2022

Theme: Religion & Politics

Discipline: American Religious History

Imagine with me an evangelical coming of age in the 1970s. Let’s call her Rachel. Her father was an independent Baptist pastor in southern Illinois, someone more interested in the prophecies of the book of Revelation than in Republican Party politics. Rachel’s parents wanted her to attend Moody Bible Institute, as they had, but she instead chose a Christian liberal arts college in the Chicago area.

As a first-year student, Rachel saw a news clip in the Chicago Sun-Times about a gathering of evangelicals at the Wabash Street YMCA in November 1973. They produced a document called the Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern, which purported to be a reaffirmation of principles espoused by evangelicals of an earlier age, including opposition to racism and income inequality, concern about poverty and hunger, and support for women’s rights. Having never heard her father, or anyone else, talk about such matters, Rachel decided to dig deeper into the history of her own tradition. Through coursework and her own curiosity, reading through nineteenth-century journals in the bowels of the college library, Rachel began to stitch together a robust agenda of evangelical social reform: opposition to slavery, peace crusades, prison reform, and support for women’s equality, including voting rights. Evangelicals, it turns out, were in the vanguard of support for public education, known at the time as common schools, so that the children of those less fortunate might climb the ladder of upward mobility.

Sure, there were some outliers—unvarnished nativists and those who offered theological defenses of slavery—and some evangelical initiatives would be considered paternalist, even colonialist, by contemporary standards. But the overall tapestry was lush and bespoke a concern for those Jesus called “the least of these.”

How is it that Rachel had never heard of these things? She put that question to her father during Christmas break of her sophomore year. He had not heard of them either. His heroes, he said, were Dwight L. Moody and Ruben A. Torrey. He had only a dim recollection of hearing names like Sarah Lankford or Charles Grandison Finney.

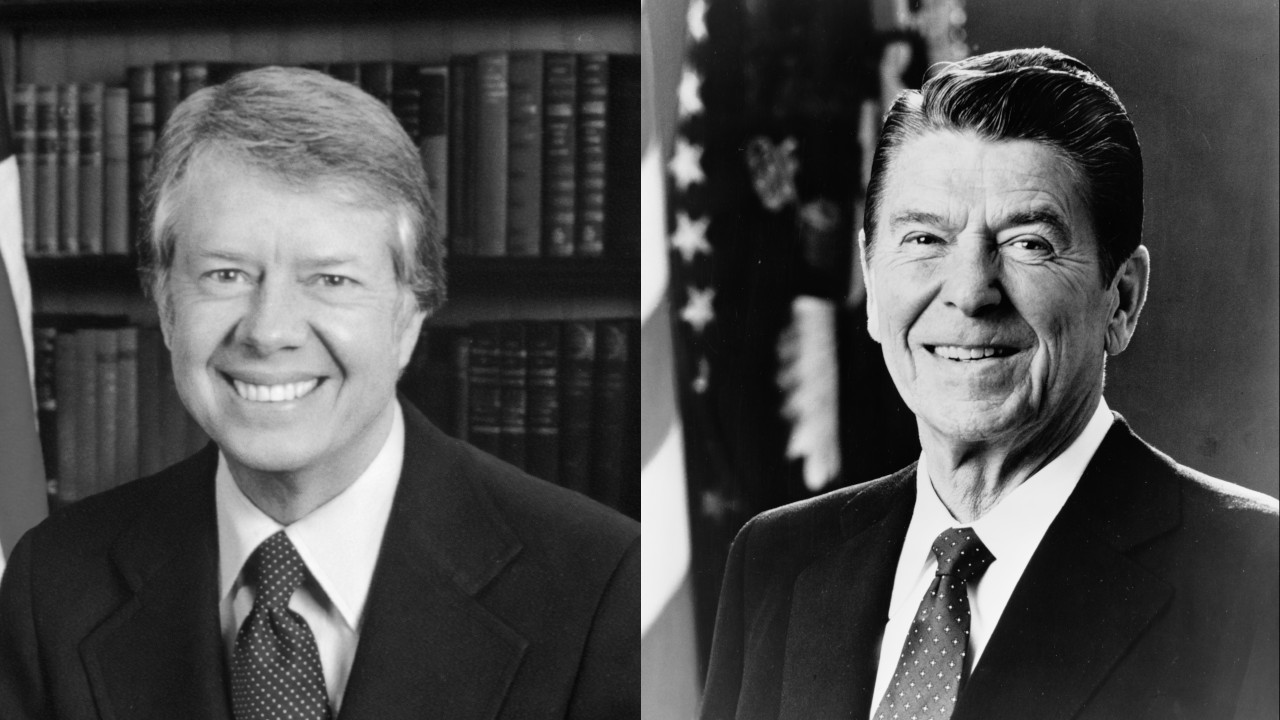

Rachel’s campus was a pretty insular place. She remembered reading The Last Year of the War and thinking that pretty much described her own college experience. But sometime in her sophomore year she began to hear about a candidate for the Democratic nomination who claimed to be a “born again” Christian. That was remarkable in itself, but what really caught her attention was that Jimmy Carter did not seem ashamed of his born again experience as Rachel had been in high school. In the course of the campaign, Governor Carter could be maddeningly vague about some of his policies, but his general disposition on matters like race and poverty and peace and women’s rights seemed to Rachel remarkably consistent with the nineteenth-century evangelicals she was studying.

Rachel decided to write her senior thesis on Finney who, she concluded, was the most influential evangelical of the nineteenth century. Her research brought more revelations. Finney’s understanding of the Christian faith led him to a suspicion of capitalism because it was suffused with avarice and selfishness. Finney allowed that “the business aims and practices of business men are almost universally an abomination in the sight of God.” What are the principles of those who engage in business? Finney asked. “Seeking their own ends; doing something not for others, but for self.” Finney enumerated “another thing which is highly esteemed among men, yet is an abomination before God,” namely “selfish ambition.”

Finney was arguing, Rachel decided, that a “Christian businessman” was an oxymoron because capitalism elevated avarice over altruism. Rachel was absolutely certain she had never heard such sentiments from her father’s pulpit.

In November of her senior year, Rachel cast her first vote ever—for a fellow evangelical, Jimmy Carter. The faculty adjudged her thesis worthy of its highest prize, and Rachel decided to enter graduate school. About this time, as she began to hear that evangelicals were starting to organize politically, Rachel was encouraged. Finally, it seemed, evangelicals were turning away from premillennialism and its theology of despair to reclaim their noble heritage of nineteenth-century activism.

But as she tuned into the rhetoric, she heard something very different. Evangelicals should organize politically, she heard, not to care for those on the margins but in defense of free-market capitalism, which Jerry Falwell declared was “God’s way of doing things.” Huh? Where did this come from? She also learned that the United States was on a slippery slope of moral decay, infected with something called “secular humanism,” which seemed to have its origins in a Supreme Court decision handed down on January 22, 1973.

Rachel tried to recall that turning point. She had been a senior in high school strategizing at the time how she could persuade her parents to allow her to attend the prom. She was building a pyramid of arguments toward that end, the crowning appeal being, “But what if I promise not to dance?” She remembered hearing nothing whatsoever about abortion or Roe v. Wade. Abortion, after all, was a Catholic issue, not an evangelical one.

Rachel’s curiosity about her own tradition, and especially about the origins of the Religious Right, drove her studies. Over the course of several years, she learned that abortion had nothing to do with evangelical activism in the 1970s. Two successive editors of Christianity Today expressed qualified support for abortion rights, and the Southern Baptist Convention, hardly a redoubt of liberalism, passed a resolution calling for the legalization of abortion in 1971, which they reaffirmed in 1974 and again in 1976. Falwell himself, by his own admission, did not preach his first anti-abortion sermon until February 26, 1978, more than five years after Roe v. Wade. Even James Dobson, who later became an implacable foe of abortion, acknowledged in 1973 that the Bible was silent on the matter and therefore it was plausible for an evangelical to believe that “a developing embryo or fetus was not regarded as a full human being.”

If not abortion, what was the catalyst for the Religious Right? Here, Rachel’s research uncovered an ugly truth: It was the defense of racial segregation in evangelical institutions, especially Bob Jones University, that politicized evangelical leaders in the 1970s. Abortion had nothing to do with it; opposition to abortion was added later, just in time for the 1980 election, as a way of diverting attention from the real origins of the movement.

And now, forty years after evangelicals abandoned one of their own in favor of a divorced and remarried Hollywood actor, Rachel began to see more clearly a line of connection from there to the present. What mystifies her to this day, however, is why evangelicals chose to neglect their own heritage, one that would have taken them in a very different direction.